Chapter 23 Bayesian data analysis 2

23.1 Learning goals

- Building Bayesian models with

brms.- Model evaluation:

- Visualizing and interpreting results.

- Testing hypotheses.

- Inference evaluation: Did things work out?

- Model evaluation:

23.2 Load packages and set plotting theme

library("knitr") # for knitting RMarkdown

library("kableExtra") # for making nice tables

library("janitor") # for cleaning column names

library("tidybayes") # tidying up results from Bayesian models

library("brms") # Bayesian regression models with Stan

library("patchwork") # for making figure panels

library("GGally") # for pairs plot

library("broom.mixed") # for tidy lmer results

library("bayesplot") # for visualization of Bayesian model fits

library("modelr") # for modeling functions

library("lme4") # for linear mixed effects models

library("afex") # for ANOVAs

library("car") # for ANOVAs

library("emmeans") # for linear contrasts

library("ggeffects") # for help with logistic regressions

library("titanic") # titanic dataset

library("gganimate") # for animations

library("parameters") # for getting parameters

library("transformr") # for gganimate

# install via: devtools::install_github("thomasp85/transformr")

library("tidyverse") # for wrangling, plotting, etc. theme_set(theme_classic() + # set the theme

theme(text = element_text(size = 20))) # set the default text size

opts_chunk$set(comment = "",

fig.show = "hold")

options(dplyr.summarise.inform = F)

# set default color scheme in ggplot

options(ggplot2.discrete.color = RColorBrewer::brewer.pal(9,"Set1"))23.3 Load data sets

# poker

df.poker = read_csv("data/poker.csv") %>%

mutate(skill = factor(skill,

levels = 1:2,

labels = c("expert", "average")),

skill = fct_relevel(skill, "average", "expert"),

hand = factor(hand,

levels = 1:3,

labels = c("bad", "neutral", "good")),

limit = factor(limit,

levels = 1:2,

labels = c("fixed", "none")),

participant = 1:n()) %>%

select(participant, everything())

# sleep

df.sleep = sleepstudy %>%

as_tibble() %>%

clean_names() %>%

mutate(subject = as.character(subject)) %>%

select(subject, days, reaction) %>%

bind_rows(tibble(subject = "374",

days = 0:1,

reaction = c(286, 288)),

tibble(subject = "373",

days = 0,

reaction = 245))

# titanic

df.titanic = titanic_train %>%

clean_names() %>%

mutate(sex = as.factor(sex))

# politeness

df.politeness = read_csv("data/politeness_data.csv") %>%

rename(pitch = frequency)23.4 Poker

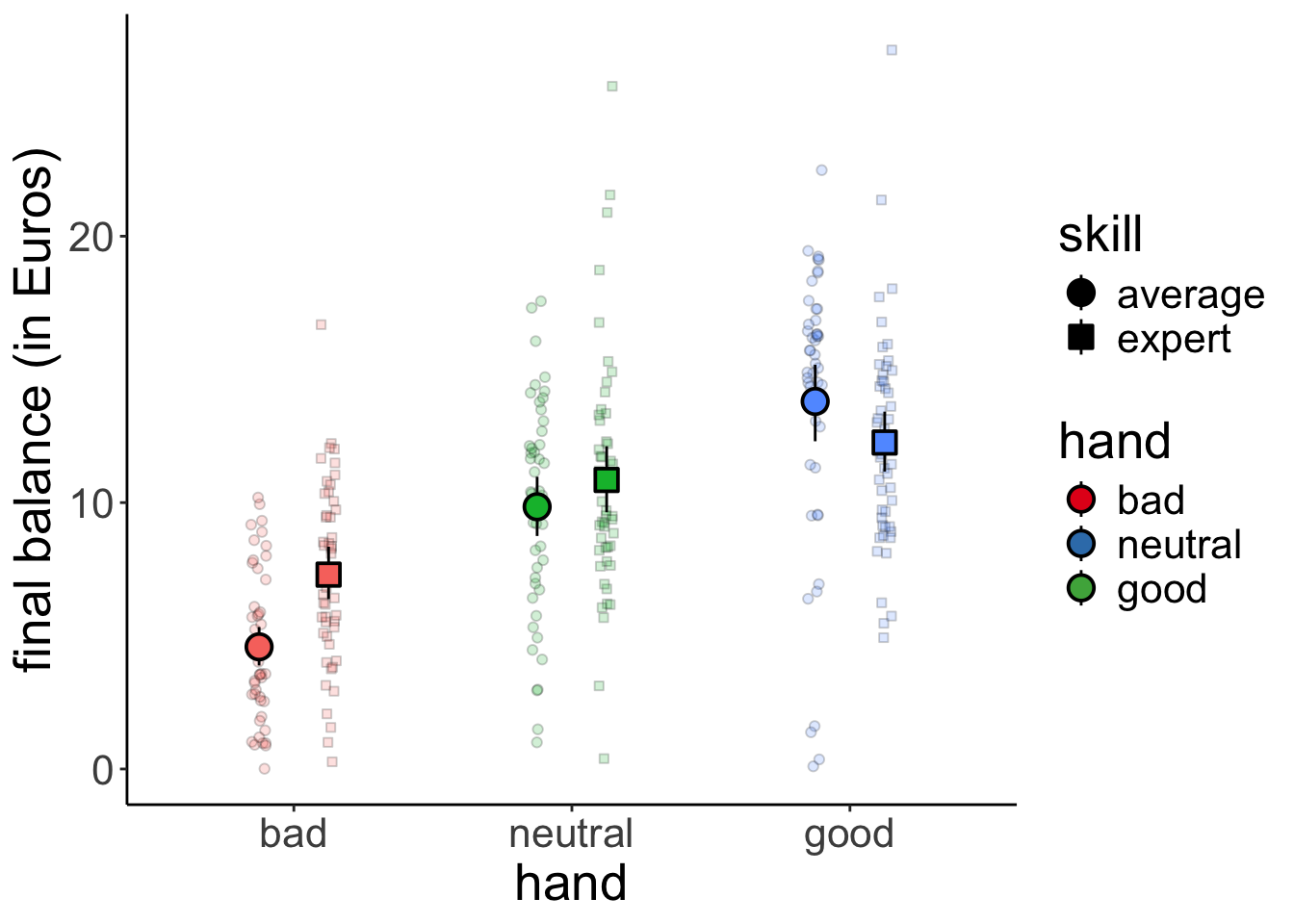

23.4.1 1. Visualize the data

Let’s visualize the data first.

set.seed(1)

df.poker %>%

ggplot(mapping = aes(x = hand,

y = balance,

fill = hand,

group = skill,

shape = skill)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.2,

position = position_jitterdodge(dodge.width = 0.5,

jitter.height = 0,

jitter.width = 0.2)) +

stat_summary(fun.data = "mean_cl_boot",

position = position_dodge(width = 0.5),

size = 1) +

labs(y = "final balance (in Euros)") +

scale_shape_manual(values = c(21, 22)) +

guides(fill = guide_legend(override.aes = list(shape = 21,

fill = RColorBrewer::brewer.pal(3, "Set1"))),

shape = guide_legend(override.aes = list(alpha = 1, fill = "black")))

23.4.2 2. Specify and fit the model

23.4.2.1 Frequentist model

And let’s now fit a simple (frequentist) ANOVA model. You have multiple options to do so:

# Option 1: Using the "afex" package

aov_ez(id = "participant",

dv = "balance",

between = c("hand", "skill"),

data = df.poker)Contrasts set to contr.sum for the following variables: hand, skillAnova Table (Type 3 tests)

Response: balance

Effect df MSE F ges p.value

1 hand 2, 294 16.16 79.17 *** .350 <.001

2 skill 1, 294 16.16 2.43 .008 .120

3 hand:skill 2, 294 16.16 7.08 *** .046 <.001

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 1# Option 2: Using the car package (here we have to remember to set the contrasts to sum

# contrasts!)

lm(balance ~ hand * skill,

contrasts = list(hand = "contr.sum",

skill = "contr.sum"),

data = df.poker) %>%

car::Anova(type = 3)Anova Table (Type III tests)

Response: balance

Sum Sq Df F value Pr(>F)

(Intercept) 28644.7 1 1772.1137 < 2.2e-16 ***

hand 2559.4 2 79.1692 < 2.2e-16 ***

skill 39.3 1 2.4344 0.1197776

hand:skill 229.0 2 7.0830 0.0009901 ***

Residuals 4752.3 294

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1# Option 3: Using the emmeans package (I like this one the best! It let's us use the

# general lm() syntax and we don't have to remember to set the contrast)

fit.lm_poker = lm(balance ~ hand * skill,

data = df.poker)

fit.lm_poker %>%

joint_tests() model term df1 df2 F.ratio p.value

hand 2 294 79.169 <.0001

skill 1 294 2.434 0.1198

hand:skill 2 294 7.083 0.0010All three options give the same result. Personally, I like Option 3 the best.

23.4.2.2 Bayesian model

Now, let’s fit a Bayesian regression model using the brm() function (starting with a simple model that only considers hand as a predictor):

fit.brm_poker = brm(formula = balance ~ 1 + hand,

data = df.poker,

seed = 1,

file = "cache/brm_poker")

# we'll use this model here later

fit.brm_poker2 = brm(formula = balance ~ 1 + hand * skill,

data = df.poker,

seed = 1,

file = "cache/brm_poker2")

fit.brm_poker %>%

summary() Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

Formula: balance ~ 1 + hand

Data: df.poker (Number of observations: 300)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 4000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 5.94 0.42 5.11 6.76 1.00 3434 2747

handneutral 4.41 0.60 3.22 5.60 1.00 3669 2860

handgood 7.09 0.61 5.91 8.27 1.00 3267 2841

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 4.12 0.17 3.82 4.48 1.00 3378 3010

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).I use the file = argument to save the model’s results so that when I run this code chunk again, the model doesn’t need to be fit again (fitting Bayesian models takes a while …). And I used the seed = argument to make this example reproducible.

23.4.2.2.1 Full specification

So far, we have used the defaults that brm() comes with and not bothered about specifiying the priors, etc.

Notice that we didn’t specify any priors in the model. By default, “brms” assigns weakly informative priors to the parameters in the model. We can see what these are by running the following command:

prior class coef group resp dpar nlpar lb ub

(flat) b

(flat) b handgood

(flat) b handneutral

student_t(3, 9.5, 5.6) Intercept

student_t(3, 0, 5.6) sigma 0

source

default

(vectorized)

(vectorized)

default

defaultWe can also get information about which priors need to be specified before fitting a model:

prior class coef group resp dpar nlpar lb ub

(flat) b

(flat) b handgood

(flat) b handneutral

student_t(3, 9.5, 5.6) Intercept

student_t(3, 0, 5.6) sigma 0

source

default

(vectorized)

(vectorized)

default

defaultHere is an example for what a more complete model specification could look like:

fit.brm_poker_full = brm(formula = balance ~ 1 + hand,

family = "gaussian",

data = df.poker,

prior = c(prior(normal(0, 10),

class = "b",

coef = "handgood"),

prior(normal(0, 10),

class = "b",

coef = "handneutral"),

prior(student_t(3, 3, 10),

class = "Intercept"),

prior(student_t(3, 0, 10),

class = "sigma")),

inits = list(list(Intercept = 0,

sigma = 1,

handgood = 5,

handneutral = 5),

list(Intercept = -5,

sigma = 3,

handgood = 2,

handneutral = 2),

list(Intercept = 2,

sigma = 1,

handgood = -1,

handneutral = 1),

list(Intercept = 1,

sigma = 2,

handgood = 2,

handneutral = -2)),

iter = 4000,

warmup = 1000,

chains = 4,

file = "cache/brm_poker_full",

seed = 1)

fit.brm_poker_full %>%

summary() Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

Formula: balance ~ 1 + hand

Data: df.poker (Number of observations: 300)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 4000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 12000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 5.96 0.41 5.15 6.76 1.00 10533 8949

handneutral 4.39 0.58 3.26 5.52 1.00 11458 9173

handgood 7.06 0.58 5.91 8.20 1.00 10754 8753

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 4.13 0.17 3.81 4.48 1.00 11877 8882

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).We can also take a look at the Stan code that the brm() function creates:

// generated with brms 2.20.4

functions {

}

data {

int<lower=1> N; // total number of observations

vector[N] Y; // response variable

int<lower=1> K; // number of population-level effects

matrix[N, K] X; // population-level design matrix

int<lower=1> Kc; // number of population-level effects after centering

int prior_only; // should the likelihood be ignored?

}

transformed data {

matrix[N, Kc] Xc; // centered version of X without an intercept

vector[Kc] means_X; // column means of X before centering

for (i in 2:K) {

means_X[i - 1] = mean(X[, i]);

Xc[, i - 1] = X[, i] - means_X[i - 1];

}

}

parameters {

vector[Kc] b; // regression coefficients

real Intercept; // temporary intercept for centered predictors

real<lower=0> sigma; // dispersion parameter

}

transformed parameters {

real lprior = 0; // prior contributions to the log posterior

lprior += normal_lpdf(b[1] | 0, 10);

lprior += normal_lpdf(b[2] | 0, 10);

lprior += student_t_lpdf(Intercept | 3, 3, 10);

lprior += student_t_lpdf(sigma | 3, 0, 10)

- 1 * student_t_lccdf(0 | 3, 0, 10);

}

model {

// likelihood including constants

if (!prior_only) {

target += normal_id_glm_lpdf(Y | Xc, Intercept, b, sigma);

}

// priors including constants

target += lprior;

}

generated quantities {

// actual population-level intercept

real b_Intercept = Intercept - dot_product(means_X, b);

}One thing worth noticing: by default, “brms” centers the predictors which makes it easier to assign a default prior over the intercept.

23.4.3 3. Model evaluation

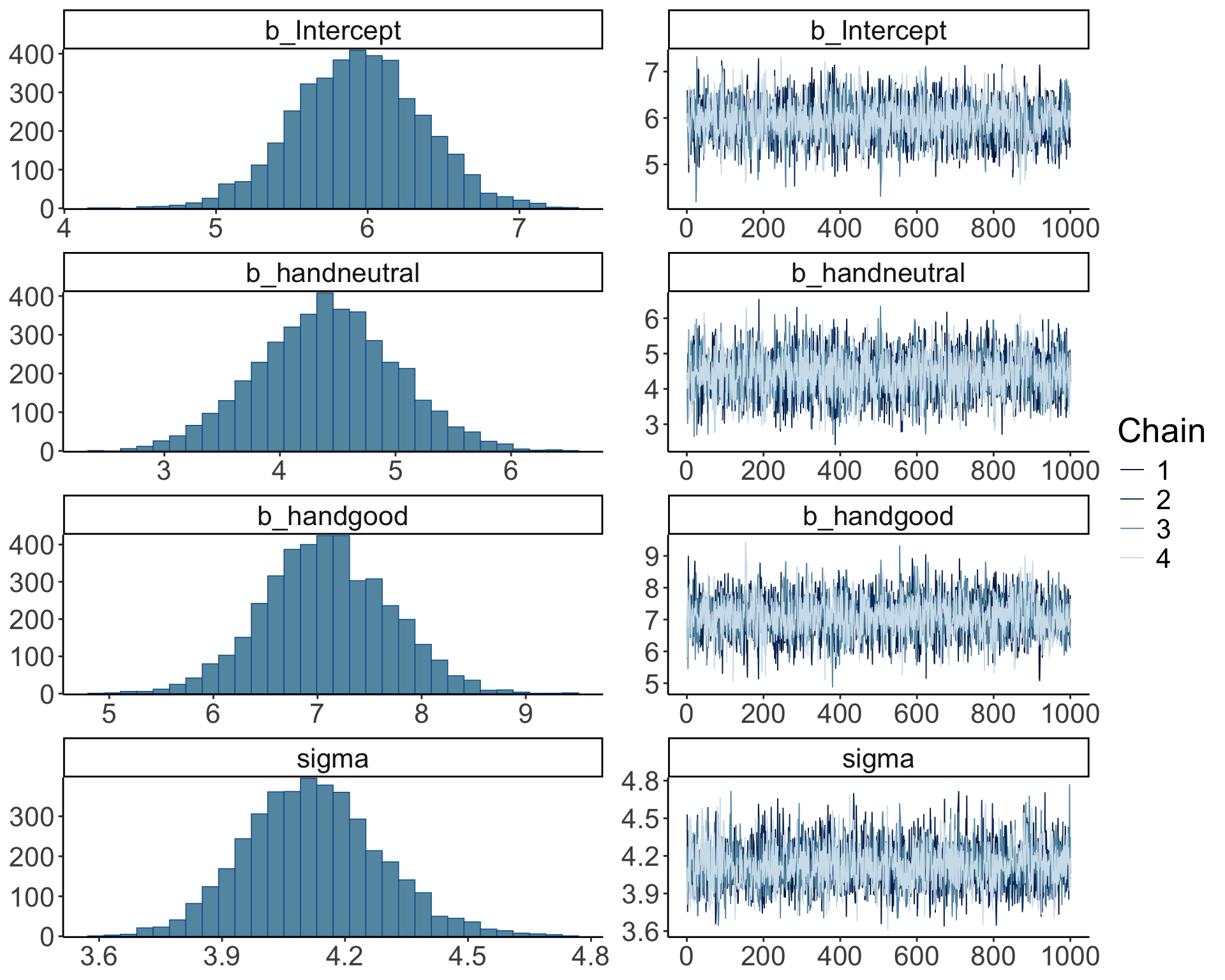

23.4.3.1 a) Did the inference work?

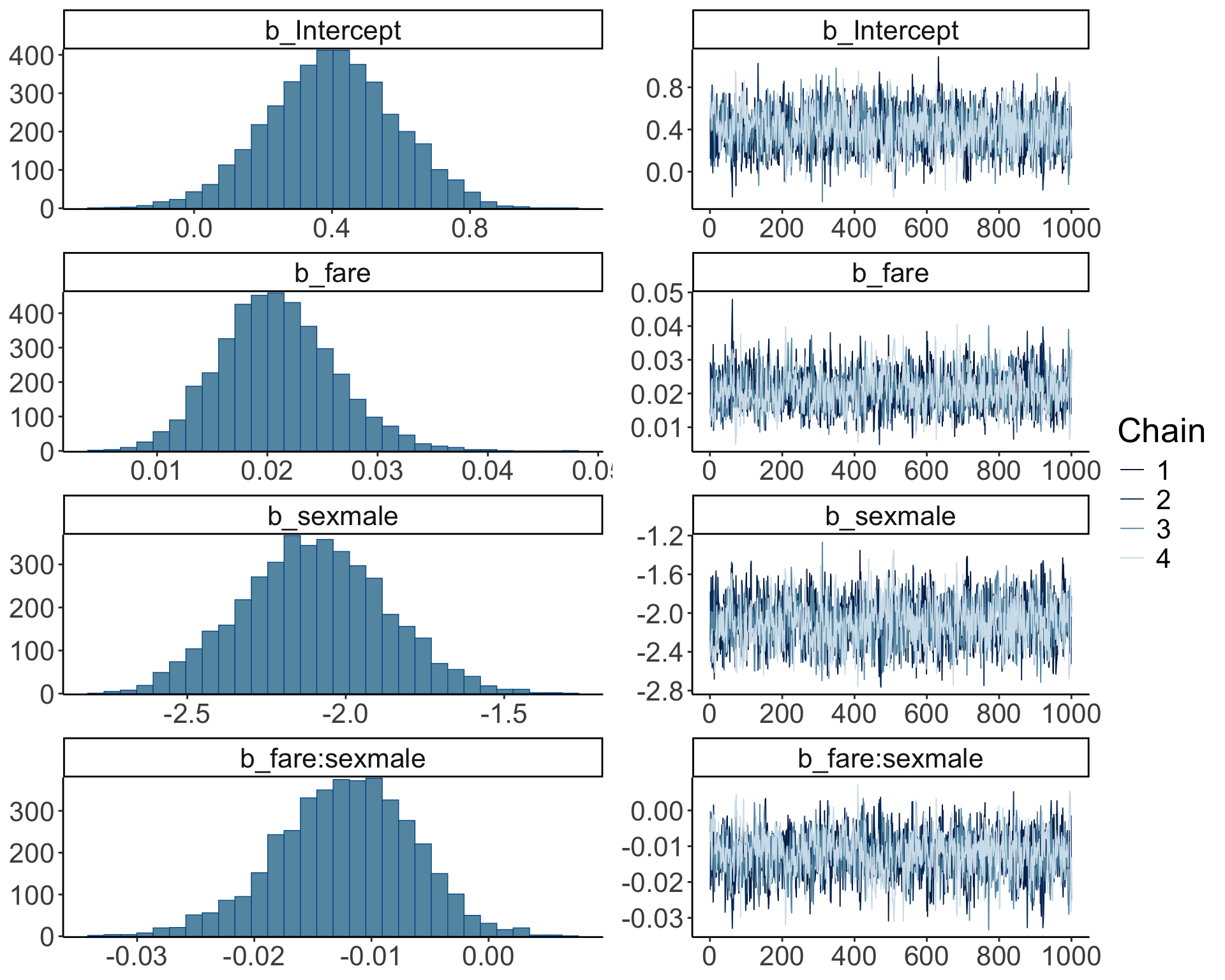

So far, we’ve assumed that the inference has worked out. We can check this by running plot() on our brm object:

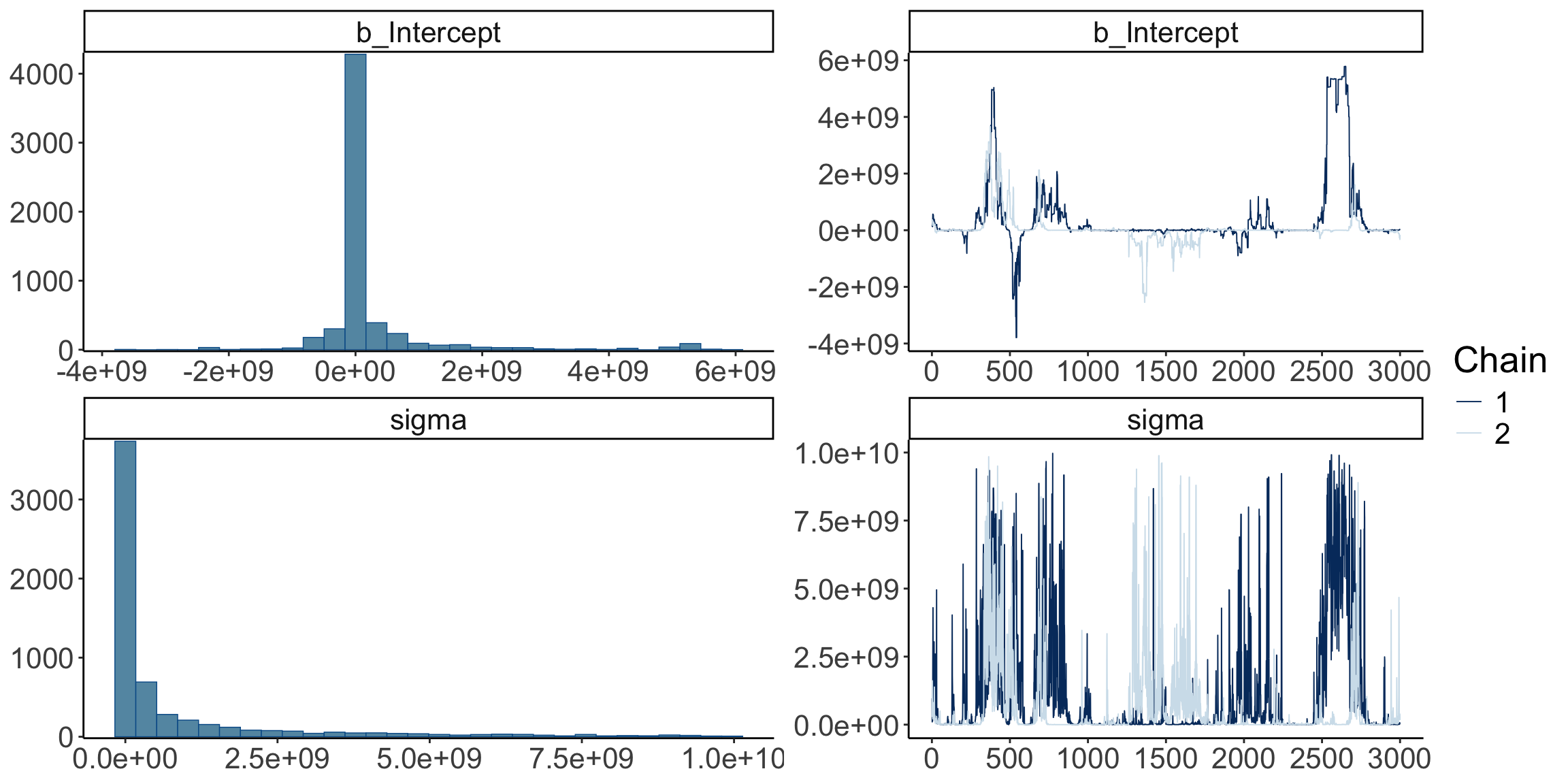

Warning: Argument 'N' is deprecated. Please use argument 'nvariables' instead.

The posterior distributions (left hand side), and the trace plots of the samples from the posterior (right hand side) look good.

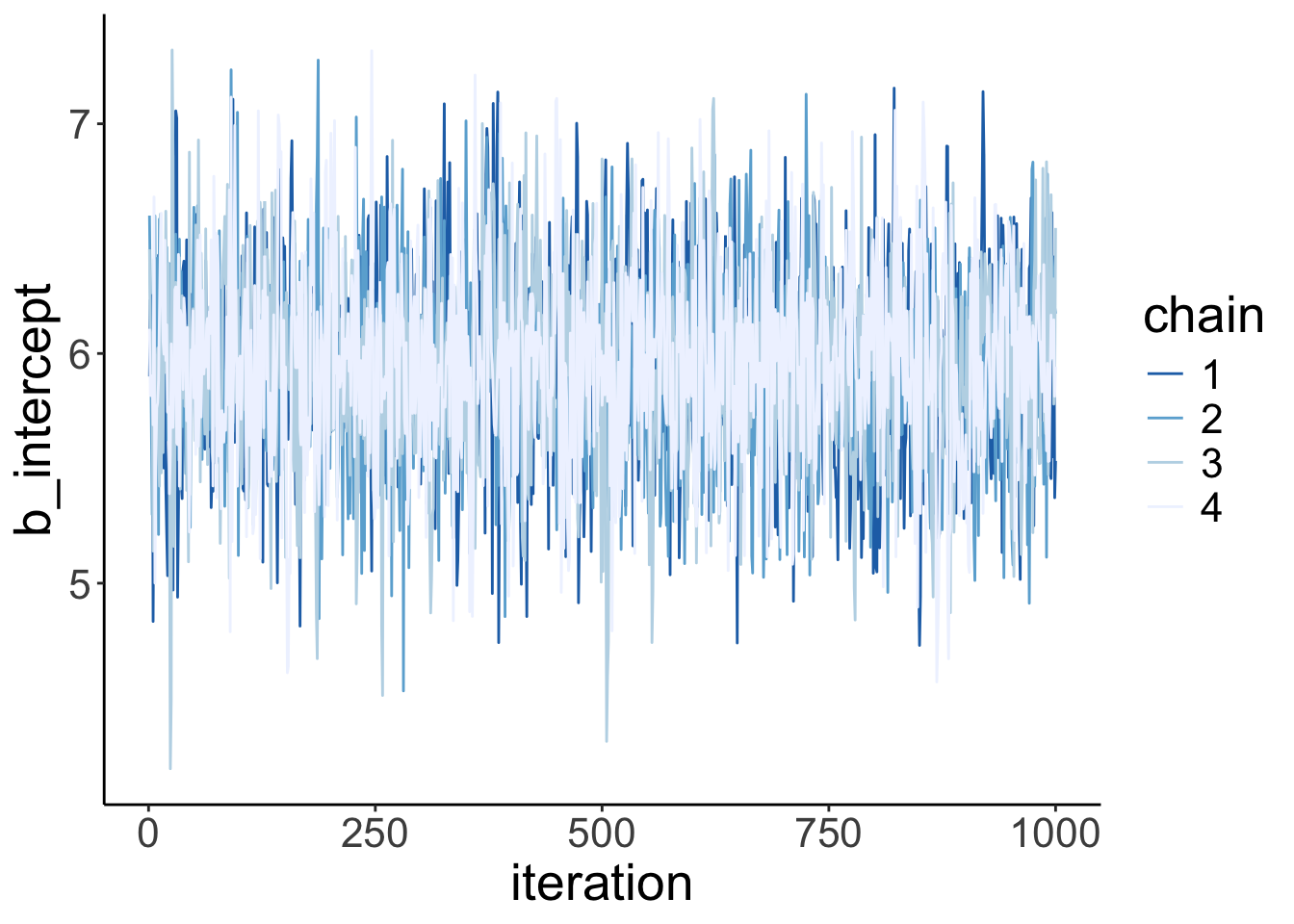

Let’s make our own version of a trace plot for one parameter in the model:

fit.brm_poker %>%

spread_draws(b_Intercept) %>%

clean_names() %>%

mutate(chain = as.factor(chain)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = iteration,

y = b_intercept,

group = chain,

color = chain)) +

geom_line() +

scale_color_brewer(type = "seq",

direction = -1)

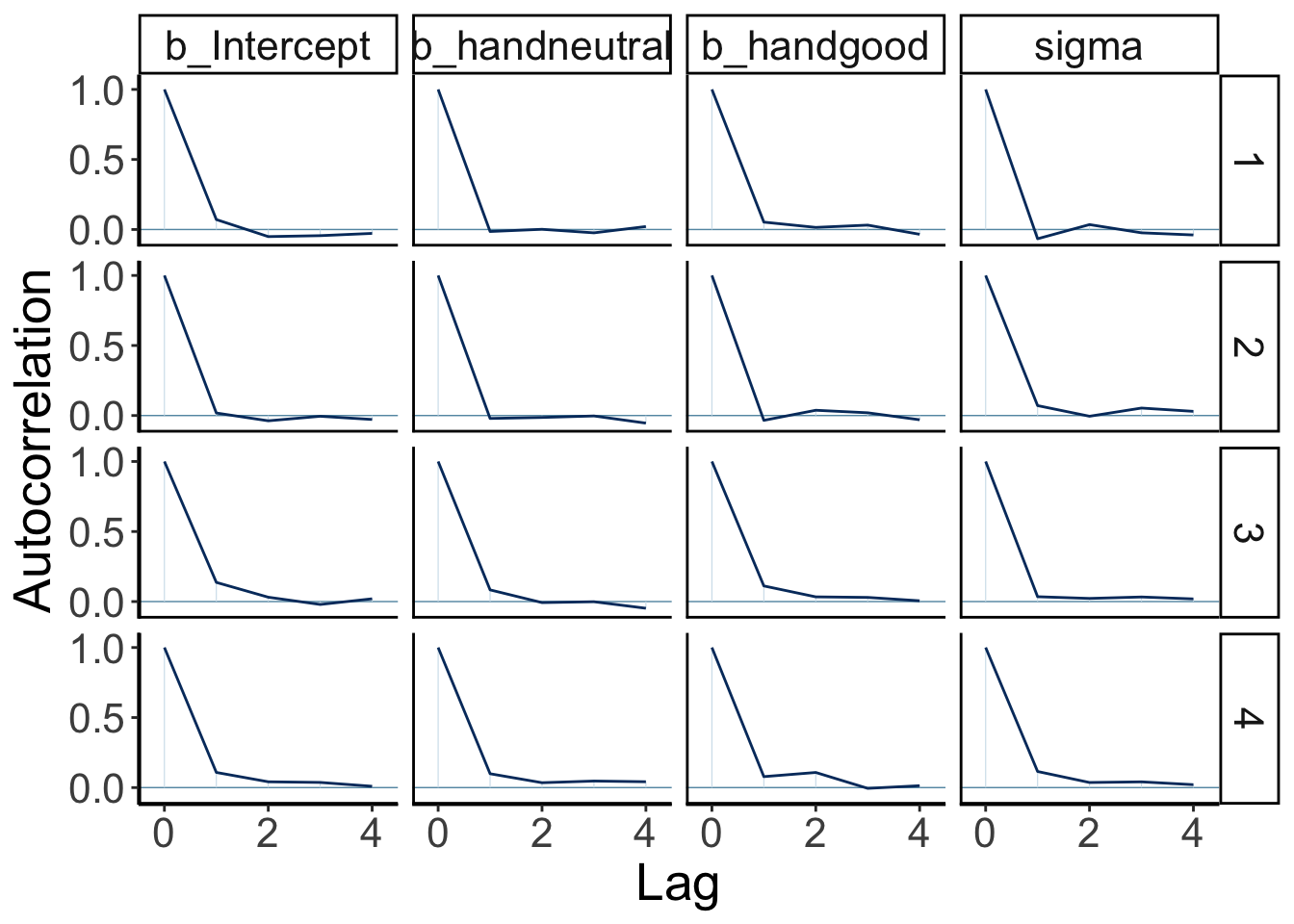

We can also take a look at the auto-correlation plot. Ideally, we want to generate independent samples from the posterior. So we don’t want subsequent samples to be strongly correlated with each other. Let’s take a look:

variables = fit.brm_poker %>%

get_variables() %>%

.[1:4]

fit.brm_poker %>%

as_draws() %>%

mcmc_acf(pars = variables,

lags = 4)

Looking good! The autocorrelation should become very small as the lag increases (indicating that we are getting independent samples from the posterior).

23.4.3.1.0.1 When things go wrong

Let’s try to fit a model to very little data (just two observations) with extremely uninformative priors:

df.data = tibble(y = c(-1, 1))

fit.brm_wrong = brm(data = df.data,

family = gaussian,

formula = y ~ 1,

prior = c(prior(uniform(-1e10, 1e10), class = Intercept),

prior(uniform(0, 1e10), class = sigma)),

inits = list(list(Intercept = 0, sigma = 1),

list(Intercept = 0, sigma = 1)),

iter = 4000,

warmup = 1000,

chains = 2,

file = "cache/brm_wrong")Let’s take a look at the posterior distributions of the model parameters:

Warning: There were 1396 divergent transitions after warmup. Increasing

adapt_delta above 0.8 may help. See

http://mc-stan.org/misc/warnings.html#divergent-transitions-after-warmup Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

Formula: y ~ 1

Data: df.data (Number of observations: 2)

Draws: 2 chains, each with iter = 4000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 6000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS

Intercept 228357056.15 984976734.30 -616012010.65 4388257793.68 1.04 45

Tail_ESS

Intercept 59

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 812525872.95 1745959463.85 282591.91 6739518200.93 1.04 44 63

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).Not looking good – The estimates and credible intervals are off the charts. And the effective samples sizes in the chains are very small.

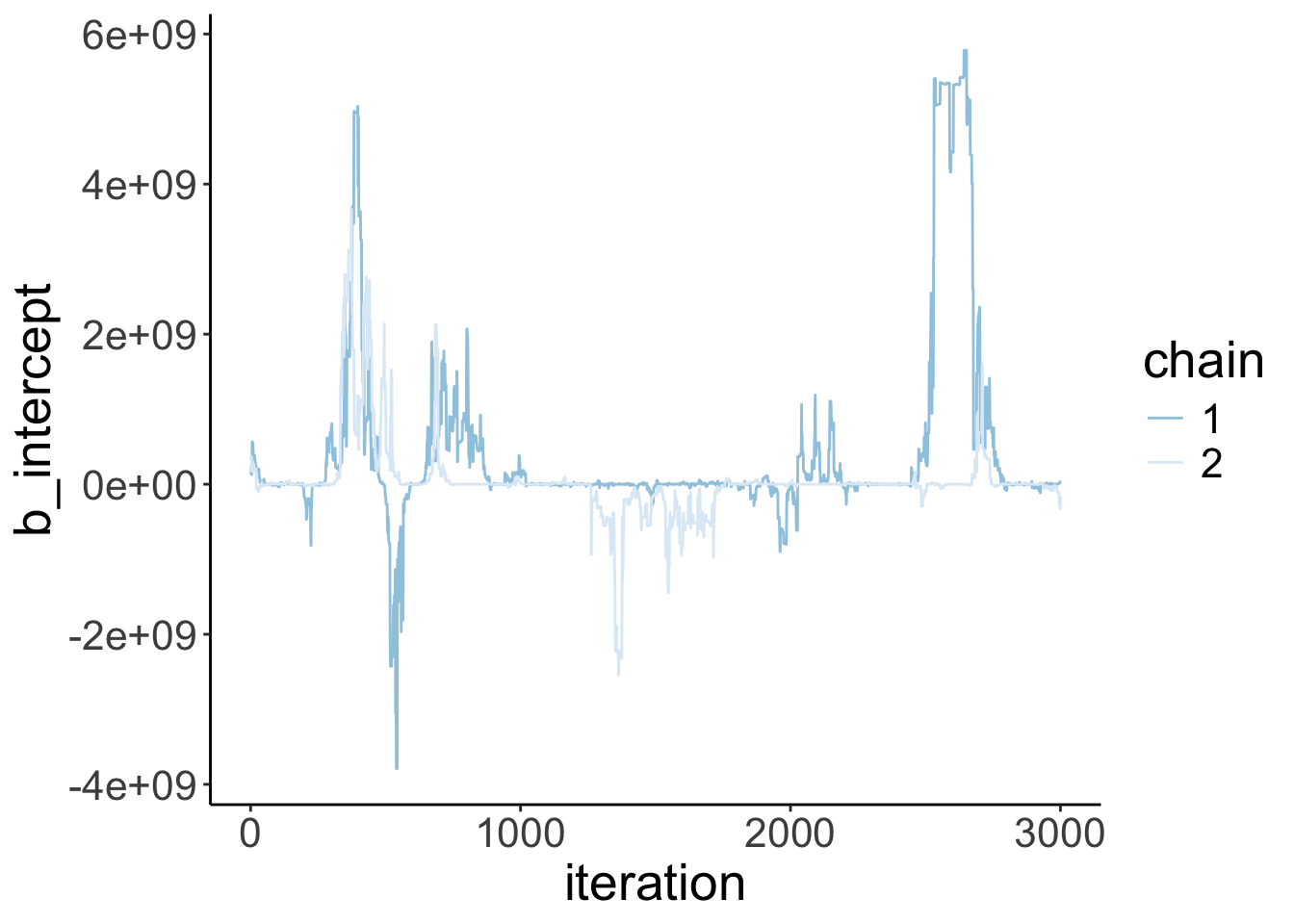

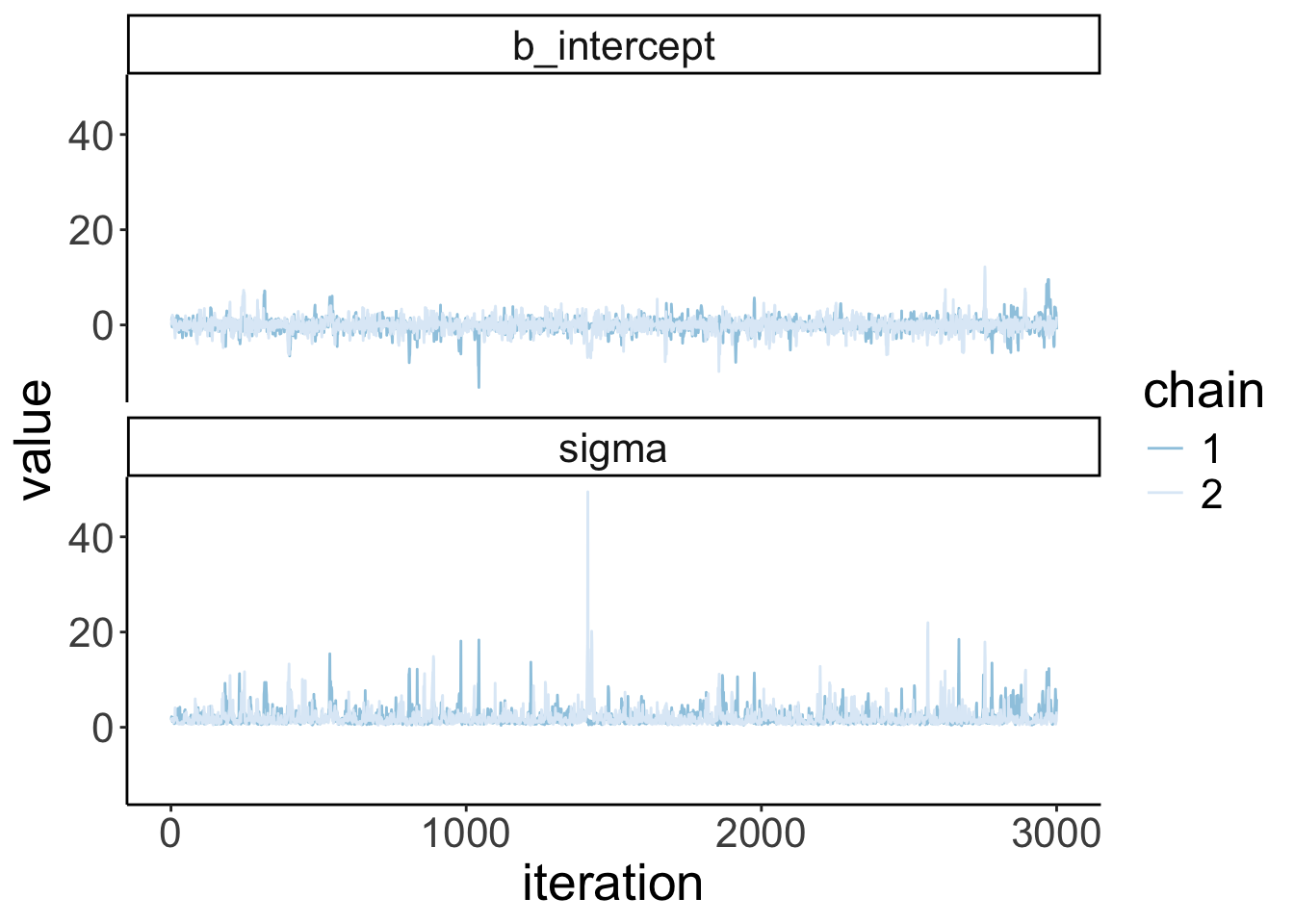

Let’s visualize the trace plots:

Warning: Argument 'N' is deprecated. Please use argument 'nvariables' instead.

fit.brm_wrong %>%

spread_draws(b_Intercept) %>%

clean_names() %>%

mutate(chain = as.factor(chain)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = iteration,

y = b_intercept,

group = chain,

color = chain)) +

geom_line() +

scale_color_brewer(direction = -1)

Given that we have so little data in this case, we need to help the model a little bit by providing some slighlty more specific priors.

fit.brm_right = brm(data = df.data,

family = gaussian,

formula = y ~ 1,

prior = c(prior(normal(0, 10), class = Intercept), # more reasonable priors

prior(cauchy(0, 1), class = sigma)),

iter = 4000,

warmup = 1000,

chains = 2,

seed = 1,

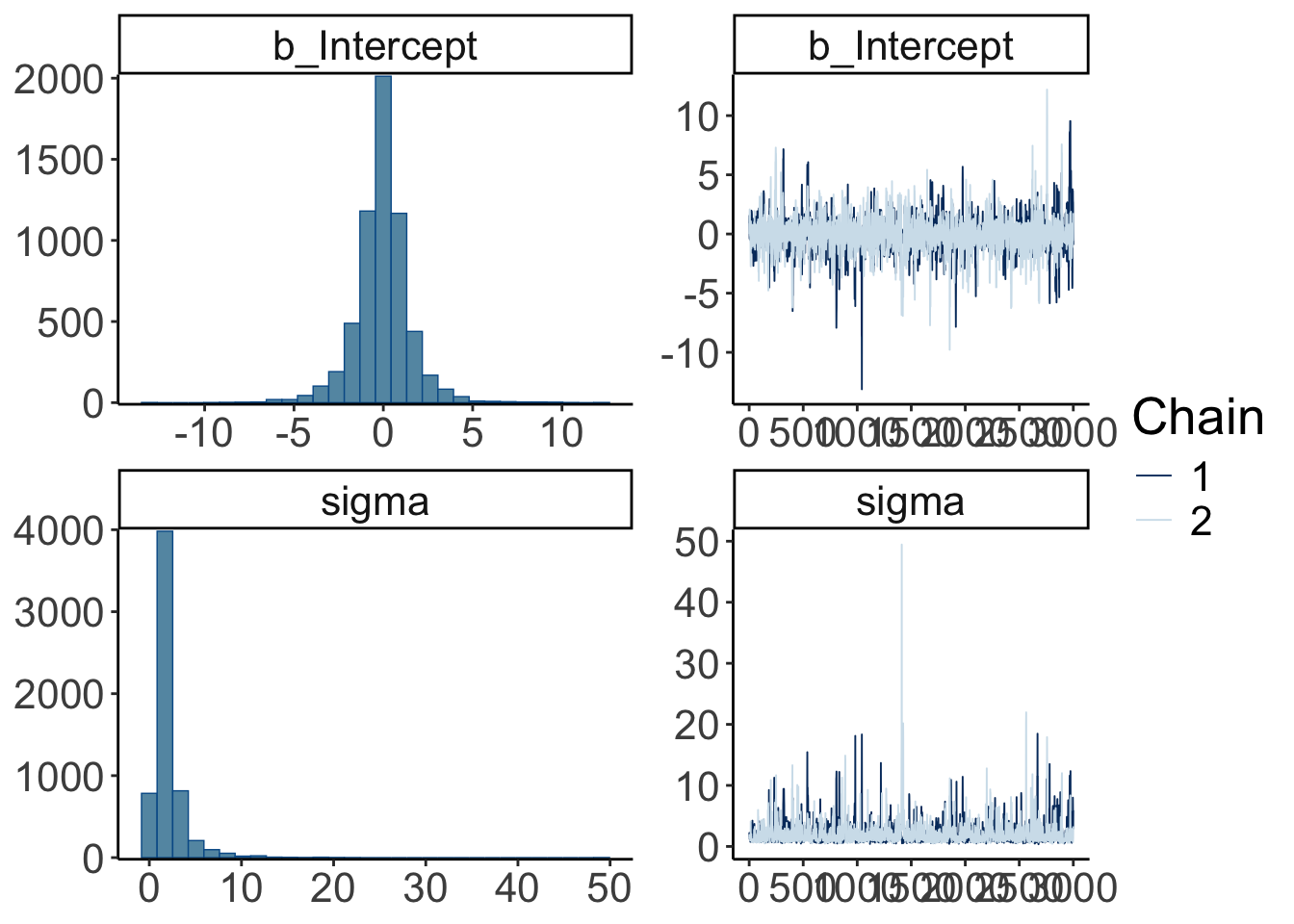

file = "cache/brm_right")Let’s take a look at the posterior distributions of the model parameters:

Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

Formula: y ~ 1

Data: df.data (Number of observations: 2)

Draws: 2 chains, each with iter = 4000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 6000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept -0.05 1.55 -3.35 3.11 1.00 1730 1300

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 2.01 1.84 0.62 6.81 1.00 1206 1568

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).This looks much better. There is still quite a bit of uncertainty in our paremeter estimates, but it has reduced dramatically.

Let’s visualize the trace plots:

Warning: Argument 'N' is deprecated. Please use argument 'nvariables' instead.

fit.brm_right %>%

spread_draws(b_Intercept, sigma) %>%

clean_names() %>%

mutate(chain = as.factor(chain)) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = c(b_intercept, sigma)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = iteration,

y = value,

group = chain,

color = chain)) +

geom_line() +

facet_wrap(vars(name), ncol = 1) +

scale_color_brewer(direction = -1)

Looking mostly good!

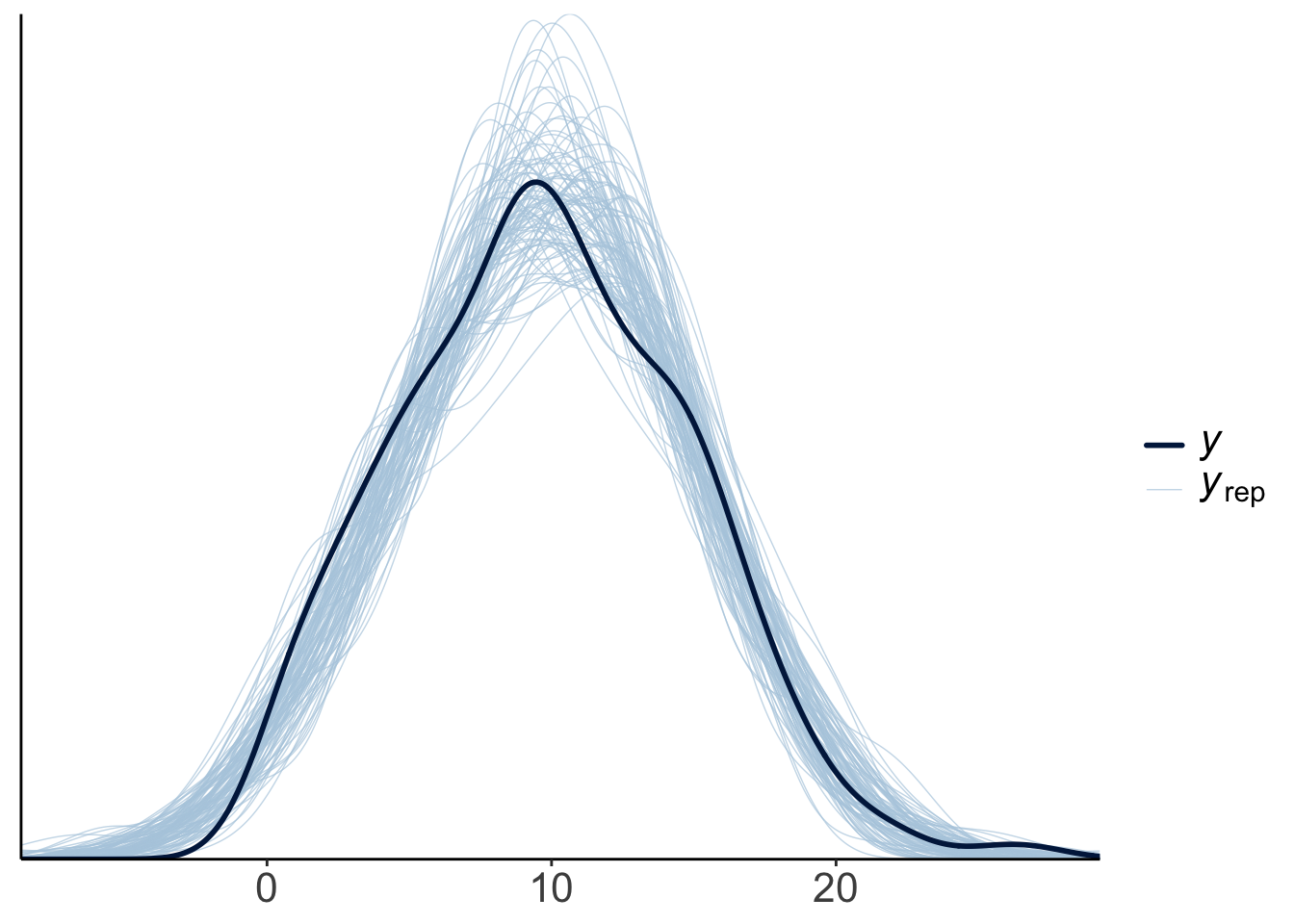

23.4.3.2 b) Visualize model predictions

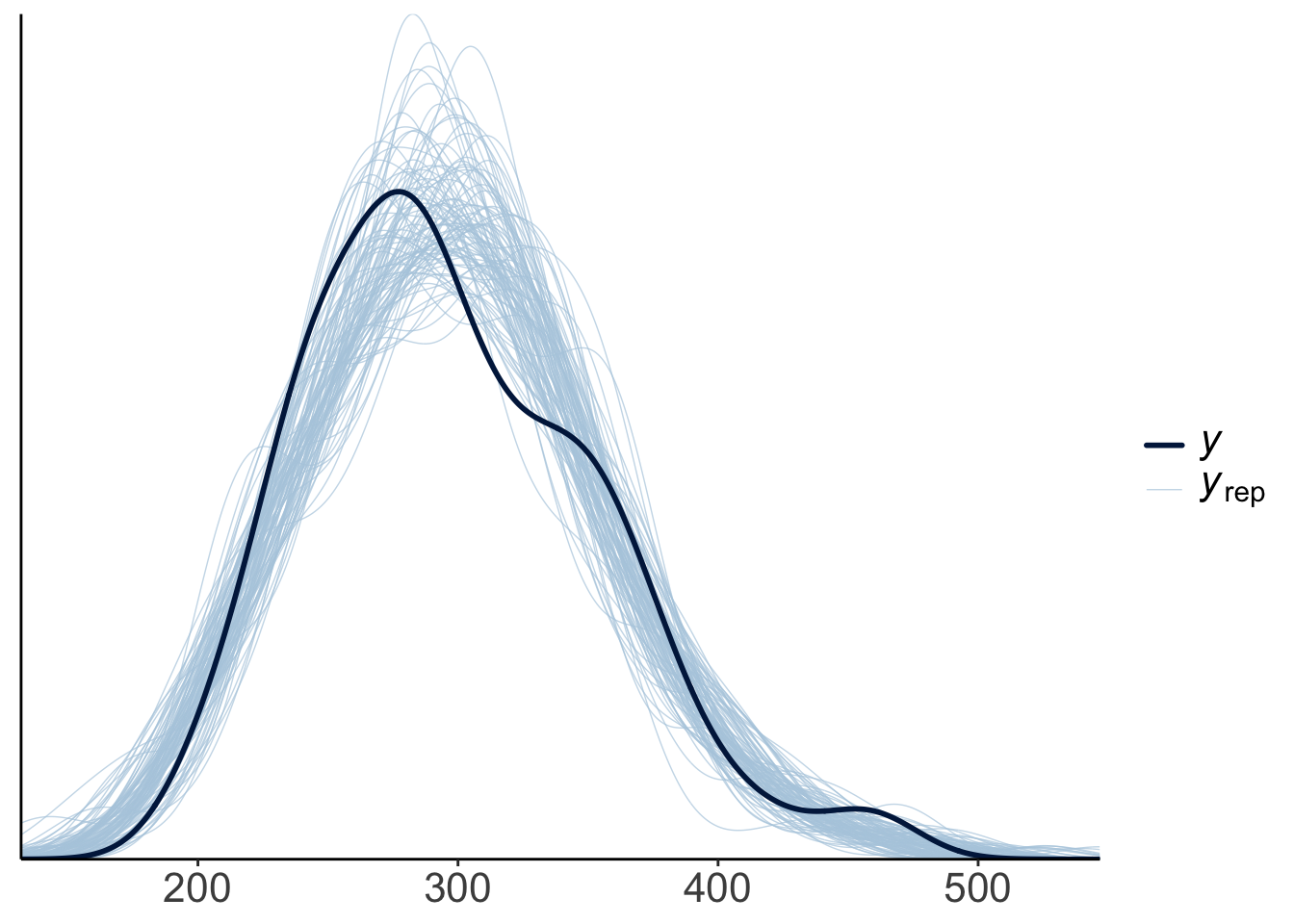

23.4.3.2.1 Posterior predictive check

To check whether the model did a good job capturing the data, we can simulate what future data the Bayesian model predicts, now that it has learned from the data we feed into it.

This looks good! The predicted shaped of the data based on samples from the posterior distribution looks very similar to the shape of the actual data.

Let’s make a hypothetical outcome plot that shows what concrete data sets the model would predict. The add_predicted_draws() function from the “tidybayes” package is helpful for generating predictions from the posterior.

df.predictive_samples = df.poker %>%

add_predicted_draws(newdata = .,

object = fit.brm_poker2,

ndraws = 10)

p = ggplot(data = df.predictive_samples,

mapping = aes(x = hand,

y = .prediction,

fill = hand,

group = skill,

shape = skill)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.2,

position = position_jitterdodge(dodge.width = 0.5,

jitter.height = 0,

jitter.width = 0.2)) +

stat_summary(fun.data = "mean_cl_boot",

position = position_dodge(width = 0.5),

size = 1) +

labs(y = "final balance (in Euros)") +

scale_shape_manual(values = c(21, 22)) +

guides(fill = guide_legend(override.aes = list(shape = 21)),

shape = guide_legend(override.aes = list(alpha = 1, fill = "black"))) +

transition_manual(.draw)

animate(p, nframes = 120, width = 800, height = 600, res = 96, type = "cairo")Warning: No renderer available. Please install the gifski, av, or magick

package to create animated output23.4.3.2.2 Prior predictive check

fit.brm_poker_prior = brm(formula = balance ~ 0 + Intercept + hand * skill,

family = "gaussian",

data = df.poker,

prior = c(prior(normal(0, 10), class = "b"),

prior(student_t(3, 0, 10), class = "sigma")),

iter = 4000,

warmup = 1000,

chains = 4,

file = "cache/brm_poker_prior",

sample_prior = "only",

seed = 1)

# generate prior samples

df.prior_samples = df.poker %>%

add_predicted_draws(newdata = .,

object = fit.brm_poker_prior,

ndraws = 10)

# plot the results as an animation

p = ggplot(data = df.prior_samples,

mapping = aes(x = hand,

y = .prediction,

fill = hand,

group = skill,

shape = skill)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.2,

position = position_jitterdodge(dodge.width = 0.5,

jitter.height = 0,

jitter.width = 0.2)) +

stat_summary(fun.data = "mean_cl_boot",

position = position_dodge(width = 0.5),

size = 1) +

labs(y = "final balance (in Euros)") +

scale_shape_manual(values = c(21, 22)) +

guides(fill = guide_legend(override.aes = list(shape = 21,

fill = RColorBrewer::brewer.pal(3, "Set1"))),

shape = guide_legend(override.aes = list(alpha = 1, fill = "black"))) +

transition_manual(.draw)

animate(p, nframes = 120, width = 800, height = 600, res = 96, type = "cairo")Warning: No renderer available. Please install the gifski, av, or magick

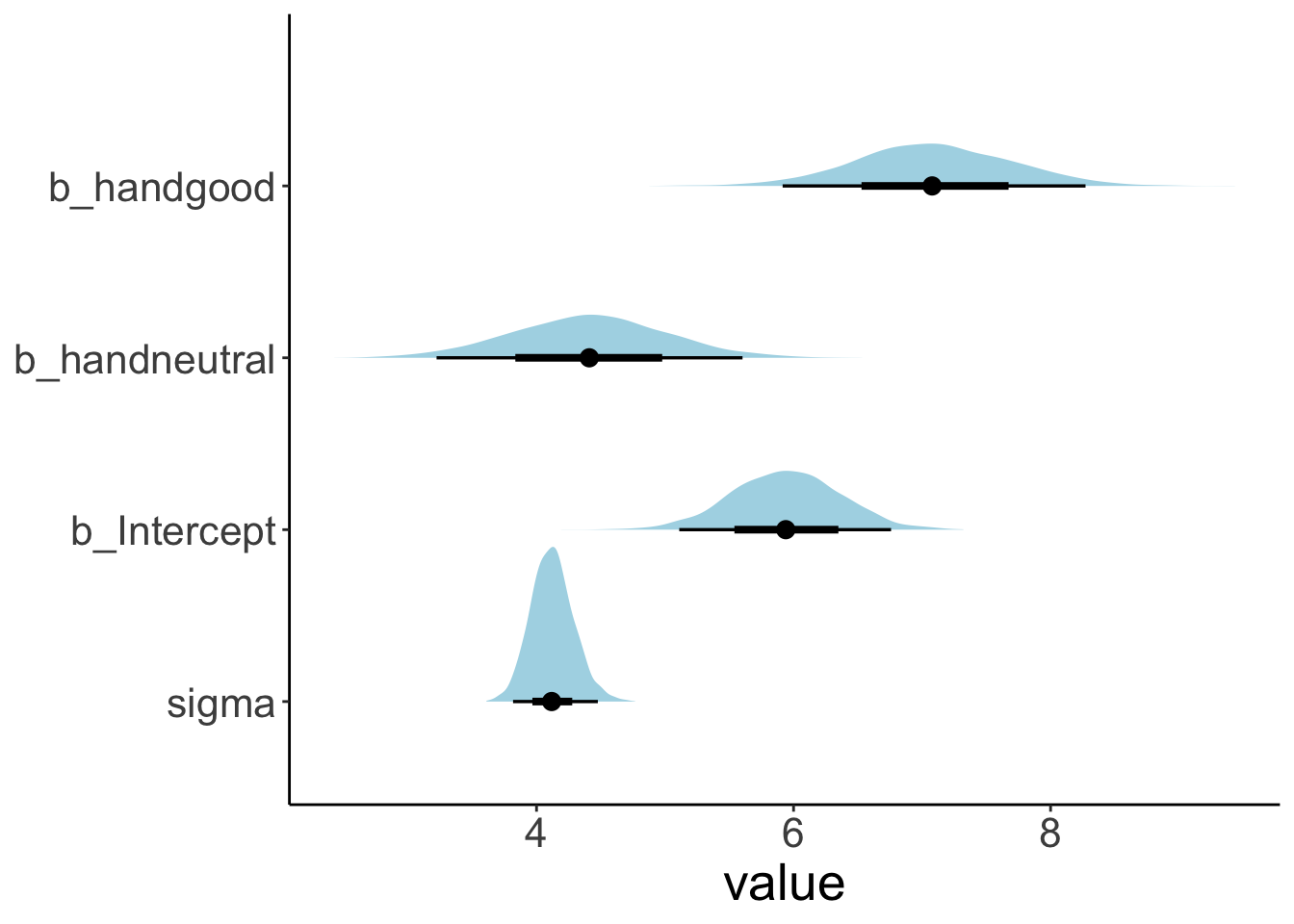

package to create animated output23.4.4 4. Interpret the model parameters

23.4.4.1 Visualize the posteriors

Let’s visualize what the posterior for the different parameters looks like. We use the stat_halfeye() function from the “tidybayes” package to do so:

fit.brm_poker %>%

as_draws_df() %>%

select(starts_with("b_"), sigma) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = everything(),

names_to = "variable",

values_to = "value") %>%

ggplot(data = .,

mapping = aes(y = fct_rev(variable),

x = value)) +

stat_halfeye(fill = "lightblue") +

theme(axis.title.y = element_blank())

23.4.4.2 Compute highest density intervals

To compute the MAP (maximum a posteriori probability) estimate and highest density interval, we use the mean_hdi() function that comes with the “tidybayes” package.

fit.brm_poker %>%

as_draws_df() %>%

select(starts_with("b_"), sigma) %>%

mean_hdi() %>%

pivot_longer(cols = -c(.width:.interval),

names_to = "index",

values_to = "value") %>%

select(index, value) %>%

mutate(index = ifelse(str_detect(index, fixed(".")), index, str_c(index, ".mean"))) %>%

separate(index, into = c("parameter", "type"), sep = "\\.") %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = type,

values_from = value)# A tibble: 4 × 4

parameter mean lower upper

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 b_Intercept 5.94 5.10 6.75

2 b_handneutral 4.41 3.21 5.58

3 b_handgood 7.09 5.92 8.27

4 sigma 4.12 3.80 4.4623.4.5 5. Test specific hypotheses

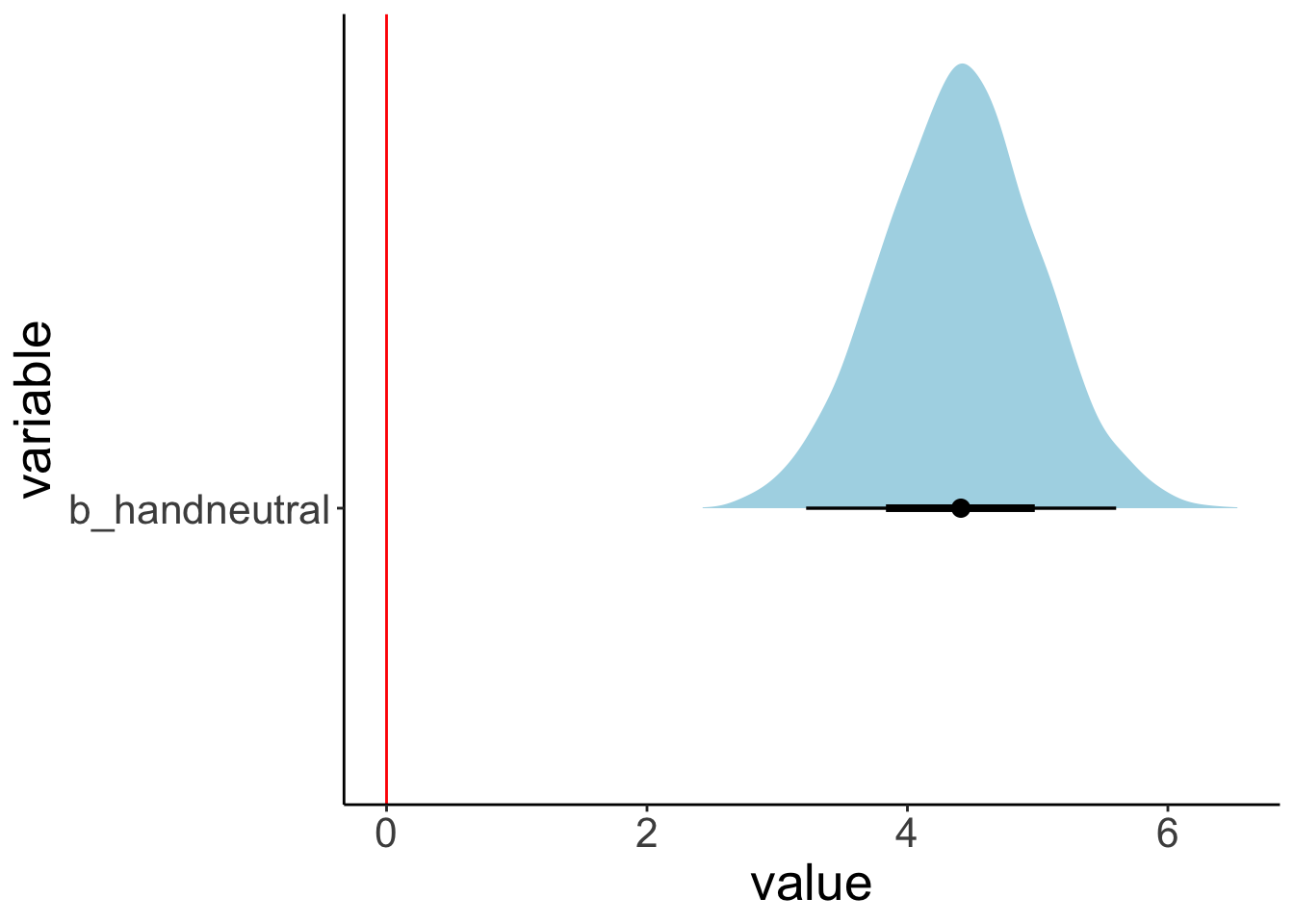

23.4.5.1 with hypothesis()

One key advantage of Bayesian over frequentist analysis is that we can test hypothesis in a very flexible manner by directly probing our posterior samples in different ways.

We may ask, for example, what the probability is that the parameter for the difference between a bad hand and a neutral hand (b_handneutral) is greater than 0. Let’s plot the posterior distribution together with the criterion:

fit.brm_poker %>%

as_draws_df() %>%

select(b_handneutral) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = everything(),

names_to = "variable",

values_to = "value") %>%

ggplot(data = .,

mapping = aes(y = variable, x = value)) +

stat_halfeye(fill = "lightblue") +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0,

color = "red")

We see that the posterior is definitely greater than 0.

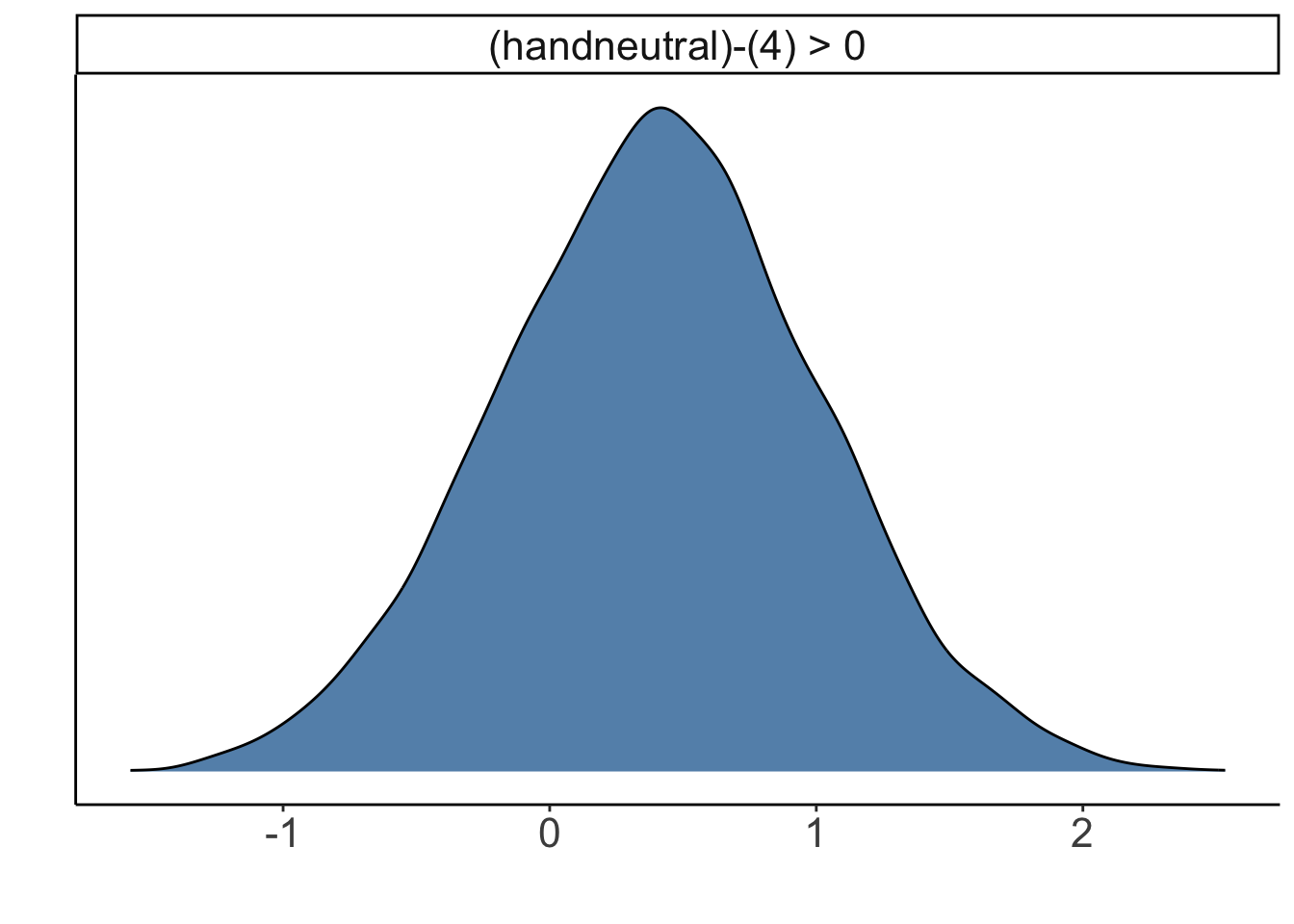

We can ask many different kinds of questions about the data by doing basic arithmetic on our posterior samples. The hypothesis() function makes this even easier. Here are some examples:

# the probability that the posterior for handneutral is less than 0

hypothesis(fit.brm_poker,

hypothesis = "handneutral < 0")Hypothesis Tests for class b:

Hypothesis Estimate Est.Error CI.Lower CI.Upper Evid.Ratio Post.Prob

1 (handneutral) < 0 4.41 0.6 3.4 5.37 0 0

Star

1

---

'CI': 90%-CI for one-sided and 95%-CI for two-sided hypotheses.

'*': For one-sided hypotheses, the posterior probability exceeds 95%;

for two-sided hypotheses, the value tested against lies outside the 95%-CI.

Posterior probabilities of point hypotheses assume equal prior probabilities.# the probability that the posterior for handneutral is greater than 4

hypothesis(fit.brm_poker,

hypothesis = "handneutral > 4") %>%

plot()

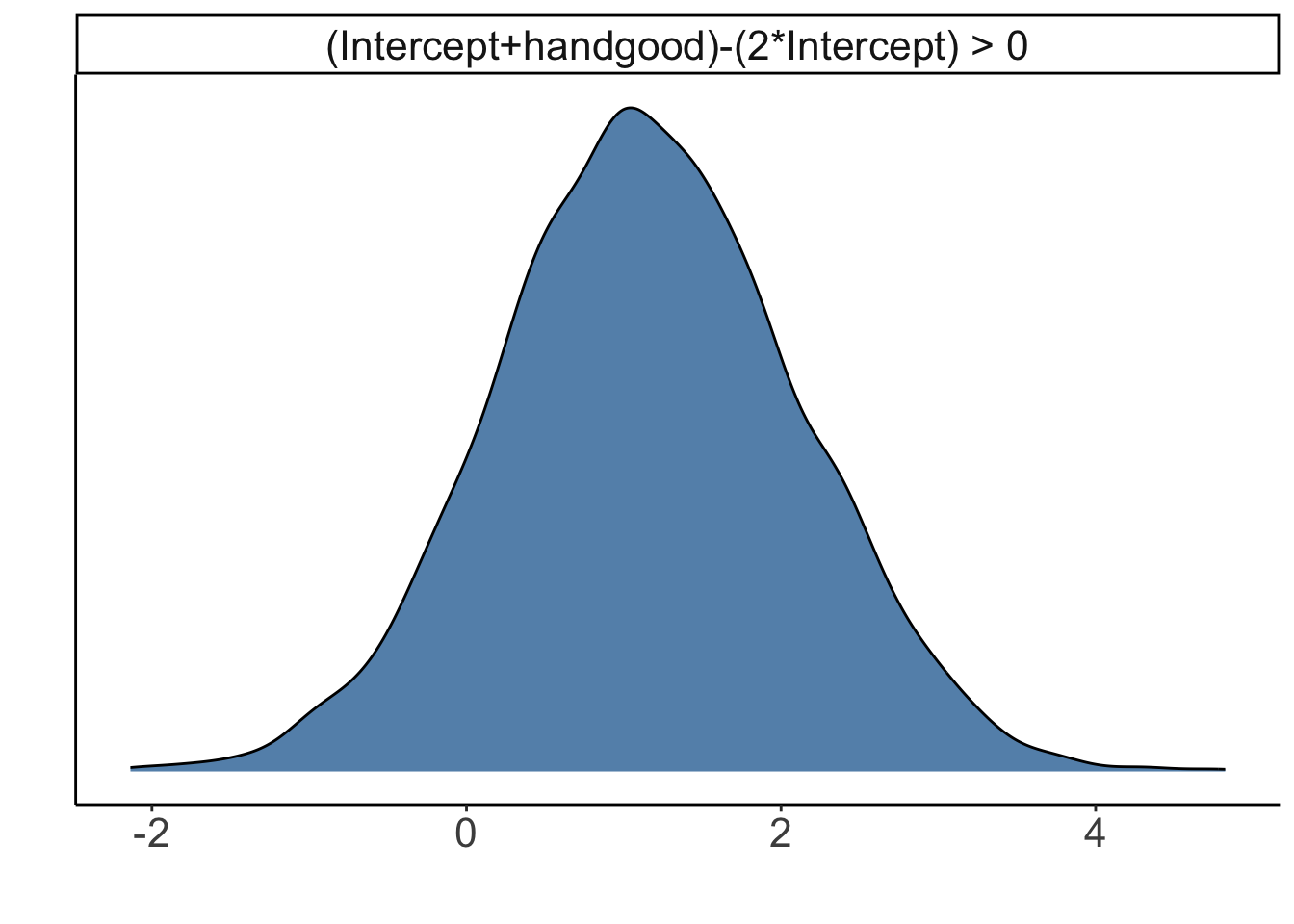

# the probability that good hands make twice as much as bad hands

hypothesis(fit.brm_poker,

hypothesis = "Intercept + handgood > 2 * Intercept")Hypothesis Tests for class b:

Hypothesis Estimate Est.Error CI.Lower CI.Upper Evid.Ratio

1 (Intercept+handgo... > 0 1.15 0.96 -0.4 2.73 7.93

Post.Prob Star

1 0.89

---

'CI': 90%-CI for one-sided and 95%-CI for two-sided hypotheses.

'*': For one-sided hypotheses, the posterior probability exceeds 95%;

for two-sided hypotheses, the value tested against lies outside the 95%-CI.

Posterior probabilities of point hypotheses assume equal prior probabilities.We can also make a plot of what the posterior distribution of the hypothesis looks like:

# the probability that neutral hands make less than the average of bad and good hands

hypothesis(fit.brm_poker,

hypothesis = "Intercept + handneutral < (Intercept + Intercept + handgood) / 2")Hypothesis Tests for class b:

Hypothesis Estimate Est.Error CI.Lower CI.Upper Evid.Ratio

1 (Intercept+handne... < 0 0.86 0.52 0.01 1.72 0.05

Post.Prob Star

1 0.05

---

'CI': 90%-CI for one-sided and 95%-CI for two-sided hypotheses.

'*': For one-sided hypotheses, the posterior probability exceeds 95%;

for two-sided hypotheses, the value tested against lies outside the 95%-CI.

Posterior probabilities of point hypotheses assume equal prior probabilities.Let’s double check one example, and calculate the result directly based on the posterior samples:

df.hypothesis = fit.brm_poker %>%

as_draws_df() %>%

clean_names() %>%

select(starts_with("b_")) %>%

mutate(neutral = b_intercept + b_handneutral,

bad_good_average = (b_intercept + b_intercept + b_handgood)/2,

hypothesis = neutral < bad_good_average)Warning: Dropping 'draws_df' class as required metadata was removed.# A tibble: 1 × 1

p

<dbl>

1 0.048523.4.5.2 with emmeans()

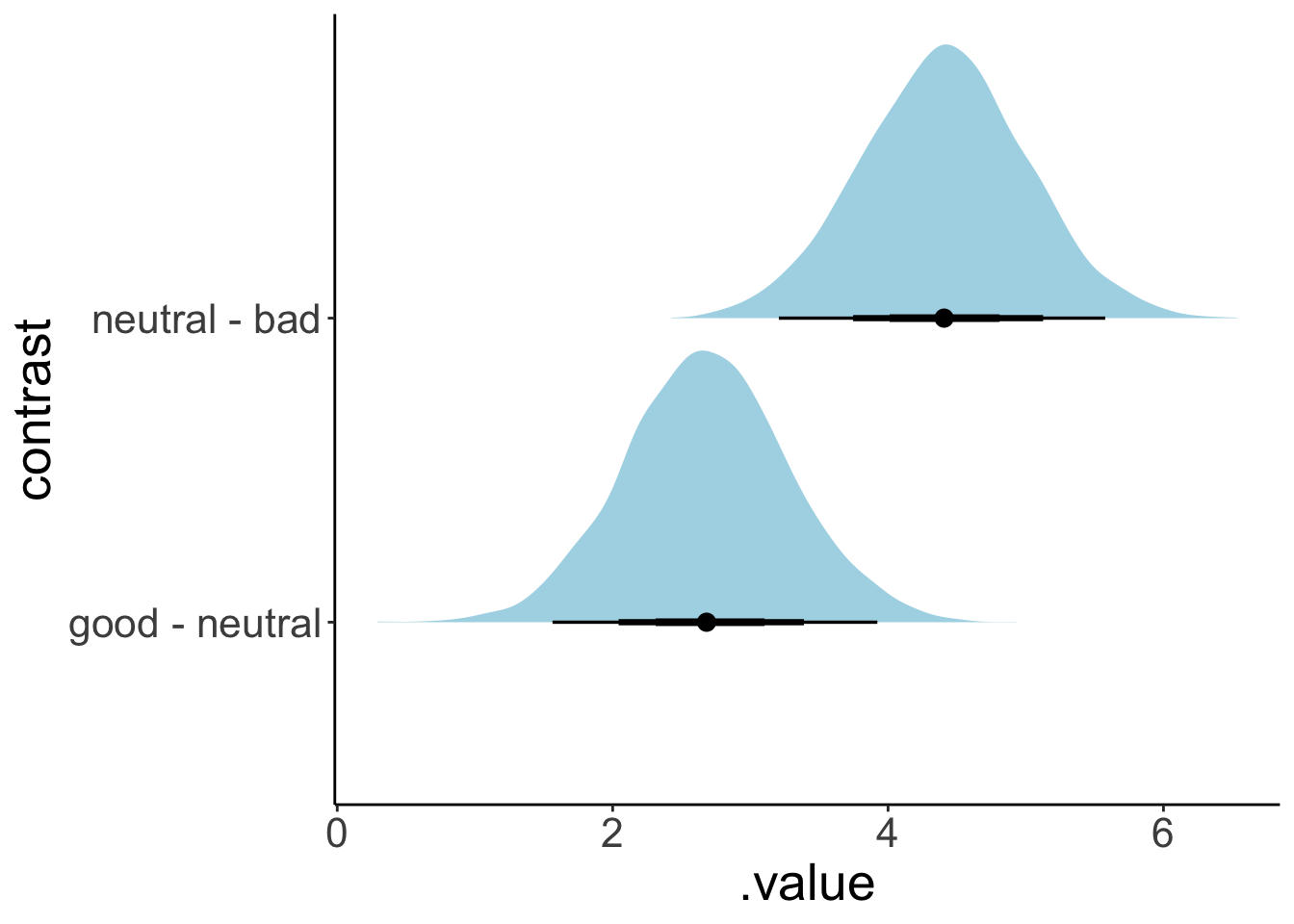

We can also use the emmeans() function to compute contrasts.

$emmeans

hand emmean lower.HPD upper.HPD

bad 5.94 5.10 6.74

neutral 10.34 9.58 11.24

good 13.03 12.19 13.87

Point estimate displayed: median

HPD interval probability: 0.95

$contrasts

contrast estimate lower.HPD upper.HPD

neutral - bad 4.41 3.21 5.58

good - neutral 2.67 1.56 3.92

Point estimate displayed: median

HPD interval probability: 0.95 Here, it computed the estimated means for each group for us, as well as the consecutive contrasts between each group.

Let’s visualize the contrasts. First, let’s just use the plot() function as it’s been adapted by the emmeans package:

To get full posterior distributions instead of summaries, we can use the “tidybayes” package like so:

fit.brm_poker %>%

emmeans(specs = consec ~ hand) %>%

pluck("contrasts") %>%

gather_emmeans_draws() %>%

ggplot(mapping = aes(y = contrast,

x = .value)) +

stat_halfeye(fill = "lightblue",

point_interval = mean_hdi,

.width = c(0.5, 0.75, 0.95))

To see whether neutral hands did differently from bad and good hands (combined), we can define the following contrast.

contrasts = list(neutral_vs_rest = c(-1, 2, -1))

fit.brm_poker %>%

emmeans(specs = "hand",

contr = contrasts) %>%

pluck("contrasts") %>%

gather_emmeans_draws() %>%

mean_hdi()# A tibble: 1 × 7

contrast .value .lower .upper .width .point .interval

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 neutral_vs_rest 1.72 -0.247 3.82 0.95 mean hdi Here, the HDP does not exclude 0.

Let’s double check that we get the same result using the hypothesis() function, or by directly computing from the posterior samples.

# using hypothesis()

fit.brm_poker %>%

hypothesis("(Intercept + handneutral)*2 < (Intercept + Intercept + handgood)")Hypothesis Tests for class b:

Hypothesis Estimate Est.Error CI.Lower CI.Upper Evid.Ratio

1 ((Intercept+handn... < 0 1.72 1.03 0.01 3.43 0.05

Post.Prob Star

1 0.05

---

'CI': 90%-CI for one-sided and 95%-CI for two-sided hypotheses.

'*': For one-sided hypotheses, the posterior probability exceeds 95%;

for two-sided hypotheses, the value tested against lies outside the 95%-CI.

Posterior probabilities of point hypotheses assume equal prior probabilities.# directly computing from the posterior

fit.brm_poker %>%

as_draws_df() %>%

clean_names() %>%

mutate(contrast = (b_intercept + b_handneutral) * 2 - (b_intercept + b_intercept + b_handgood)) %>%

summarize(contrast = mean(contrast))# A tibble: 1 × 1

contrast

<dbl>

1 1.72The emmeans() function becomes particularly useful when our model has several categorical predictors, and we are interested in comparing differences along one predictor while marginalizing over the values of the other predictor.

Let’s take a look for a model that considers both skill and hand as predictors (as well as the interaction).

fit.brm_poker2 = brm(formula = balance ~ hand * skill,

data = df.poker,

seed = 1,

file = "cache/brm_poker2")

fit.brm_poker2 %>%

summary() Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

Formula: balance ~ 1 + hand * skill

Data: df.poker (Number of observations: 300)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 4000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS

Intercept 4.58 0.56 3.48 5.69 1.00 2402

handneutral 5.26 0.79 3.72 6.86 1.00 2617

handgood 9.23 0.80 7.65 10.77 1.00 2251

skillexpert 2.73 0.78 1.17 4.25 1.00 2125

handneutral:skillexpert -1.71 1.11 -3.84 0.46 1.00 2238

handgood:skillexpert -4.28 1.12 -6.43 -2.05 1.00 2024

Tail_ESS

Intercept 2615

handneutral 2925

handgood 2504

skillexpert 2476

handneutral:skillexpert 3040

handgood:skillexpert 2295

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 4.03 0.17 3.72 4.38 1.00 3369 2728

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).In the summary table above, skillexpert captures the difference between an expert and an average player when they have a bad hand. To see whether there was a difference in expertise overall (i.e. across all three kinds of hands), we can calculate a linear contrast.

NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions$emmeans

skill emmean lower.HPD upper.HPD

average 9.41 8.77 10.0

expert 10.14 9.48 10.8

Results are averaged over the levels of: hand

Point estimate displayed: median

HPD interval probability: 0.95

$contrasts

contrast estimate lower.HPD upper.HPD

average - expert -0.722 -1.68 0.0885

Results are averaged over the levels of: hand

Point estimate displayed: median

HPD interval probability: 0.95 It looks like overall, skilled players weren’t doing much better than average players.

We can even do something like an equivalent of an ANOVA using emmeans(), like so:

model term df1 df2 F.ratio Chisq p.value

hand 2 Inf 82.446 164.892 <.0001

skill 1 Inf 2.549 2.549 0.1103

hand:skill 2 Inf 7.347 14.694 0.0006The values we get here are very similar to what we would get from a frequentist ANOVA:

Contrasts set to contr.sum for the following variables: hand, skillAnova Table (Type 3 tests)

Response: balance

Effect df MSE F ges p.value

1 hand 2, 294 16.16 79.17 *** .350 <.001

2 skill 1, 294 16.16 2.43 .008 .120

3 hand:skill 2, 294 16.16 7.08 *** .046 <.001

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '+' 0.1 ' ' 123.4.5.3 Bayes factor

Another way of testing hypothesis is via the Bayes factor. Let’s fit the two models we are interested in comparing with each other:

fit.brm_poker_bf1 = brm(formula = balance ~ 1 + hand,

data = df.poker,

save_pars = save_pars(all = T),

file = "cache/brm_poker_bf1")

fit.brm_poker_bf2 = brm(formula = balance ~ 1 + hand + skill,

data = df.poker,

save_pars = save_pars(all = T),

file = "cache/brm_poker_bf2")And then compare the models using the bayes_factor() function:

Iteration: 1

Iteration: 2

Iteration: 3

Iteration: 4

Iteration: 5

Iteration: 1

Iteration: 2

Iteration: 3

Iteration: 4Estimated Bayes factor in favor of fit.brm_poker_bf2 over fit.brm_poker_bf1: 3.82932Bayes factors don’t have a very good reputation (see here and here). Instead, the way to go these days appears to be via approximate leave one out cross-validation.

23.4.5.4 Approximate leave one out cross-validation

fit.brm_poker_bf1 = add_criterion(fit.brm_poker_bf1,

criterion = "loo",

reloo = T,

file = "cache/brm_poker_bf1")

fit.brm_poker_bf2 = add_criterion(fit.brm_poker_bf2,

criterion = "loo",

reloo = T,

file = "cache/brm_poker_bf2")

loo_compare(fit.brm_poker_bf1,

fit.brm_poker_bf2) elpd_diff se_diff

fit.brm_poker_bf2 0.0 0.0

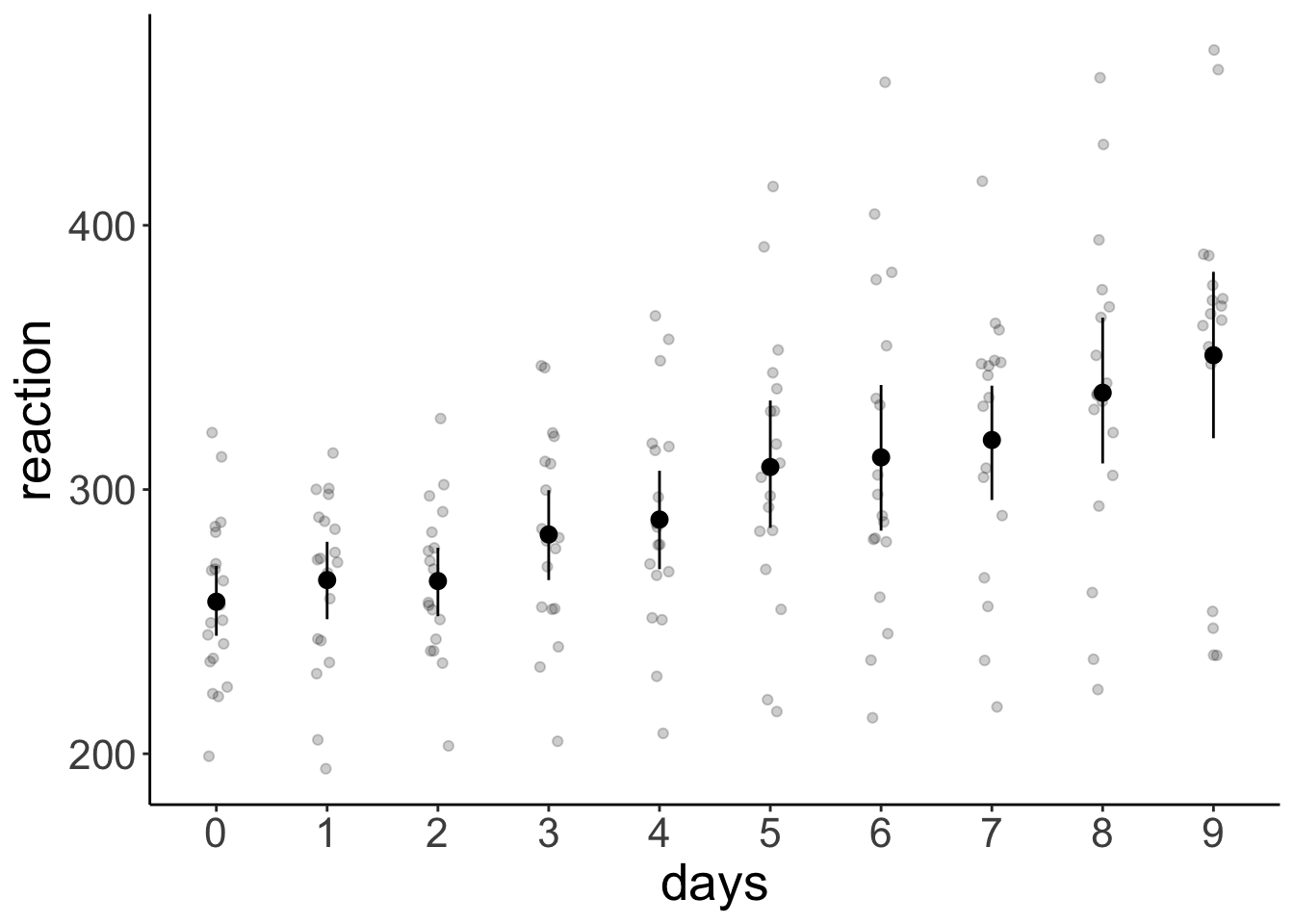

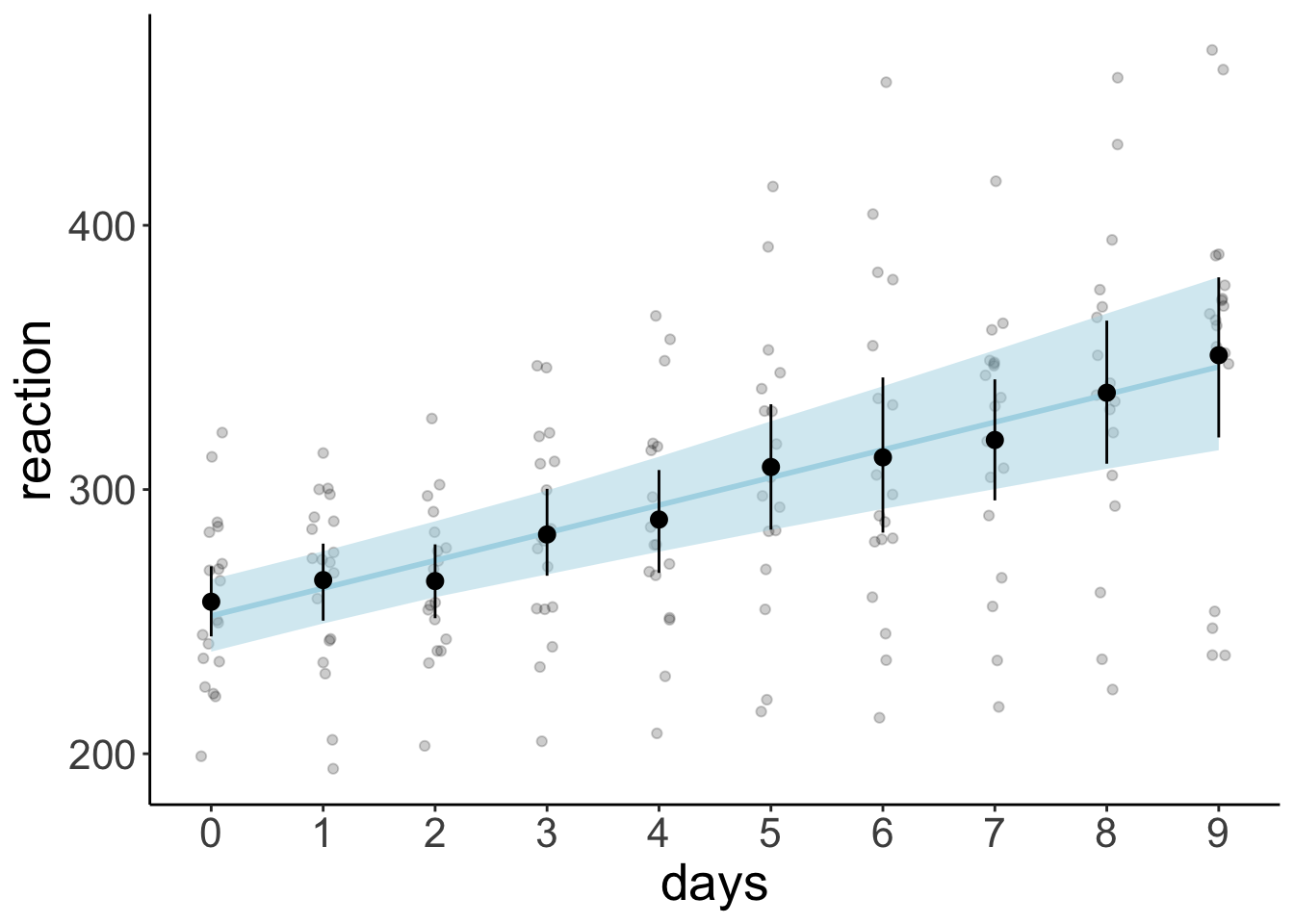

fit.brm_poker_bf1 -0.3 1.5 23.5 Sleep study

23.5.1 1. Visualize the data

set.seed(1)

ggplot(data = df.sleep %>%

mutate(days = as.factor(days)),

mapping = aes(x = days,

y = reaction)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.2,

position = position_jitter(width = 0.1)) +

stat_summary(fun.data = "mean_cl_boot")

23.5.2 2. Specify and fit the model

23.5.2.1 Frequentist analysis

fit.lmer_sleep = lmer(formula = reaction ~ 1 + days + (1 + days | subject),

data = df.sleep)

fit.lmer_sleep %>%

summary()Linear mixed model fit by REML. t-tests use Satterthwaite's method [

lmerModLmerTest]

Formula: reaction ~ 1 + days + (1 + days | subject)

Data: df.sleep

REML criterion at convergence: 1771.4

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-3.9707 -0.4703 0.0276 0.4594 5.2009

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

subject (Intercept) 582.72 24.140

days 35.03 5.919 0.07

Residual 649.36 25.483

Number of obs: 183, groups: subject, 20

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error df t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 252.543 6.433 19.295 39.257 < 2e-16 ***

days 10.452 1.542 17.163 6.778 3.06e-06 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Correlation of Fixed Effects:

(Intr)

days -0.13723.5.3 3. Model evaluation

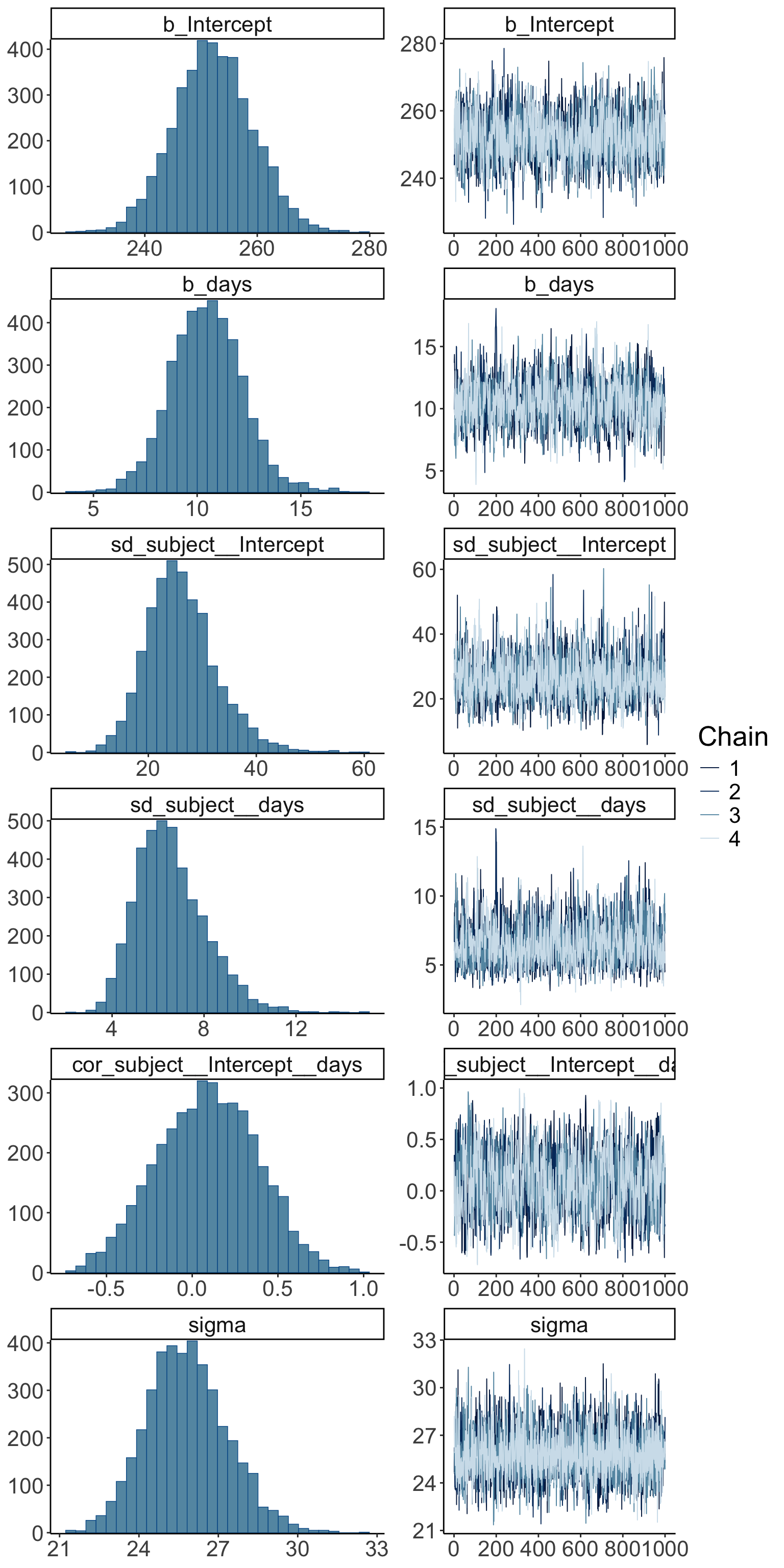

23.5.3.1 a) Did the inference work?

Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity; sigma = identity

Formula: reaction ~ 1 + days + (1 + days | subject)

Data: df.sleep (Number of observations: 183)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 4000

Multilevel Hyperparameters:

~subject (Number of levels: 20)

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sd(Intercept) 26.15 6.51 15.13 40.55 1.00 1511 2248

sd(days) 6.57 1.52 4.12 9.90 1.00 1419 2223

cor(Intercept,days) 0.09 0.29 -0.48 0.65 1.00 888 1670

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 252.18 6.95 238.65 265.96 1.00 1755 2235

days 10.47 1.75 7.07 14.00 1.00 1259 1608

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 25.82 1.54 22.96 29.05 1.00 3254 2958

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).Warning: Argument 'N' is deprecated. Please use argument 'nvariables' instead.

23.5.4 4. Interpret the parameters

# A tibble: 6 × 8

effect component group term estimate std.error conf.low conf.high

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 fixed cond <NA> (Intercept) 252. 6.95 238. 266.

2 fixed cond <NA> days 10.5 1.75 6.82 13.6

3 ran_pars cond subject sd__(Interc… 26.2 6.51 14.3 39.4

4 ran_pars cond subject sd__days 6.57 1.52 4.00 9.67

5 ran_pars cond subject cor__(Inter… 0.0909 0.293 -0.491 0.635

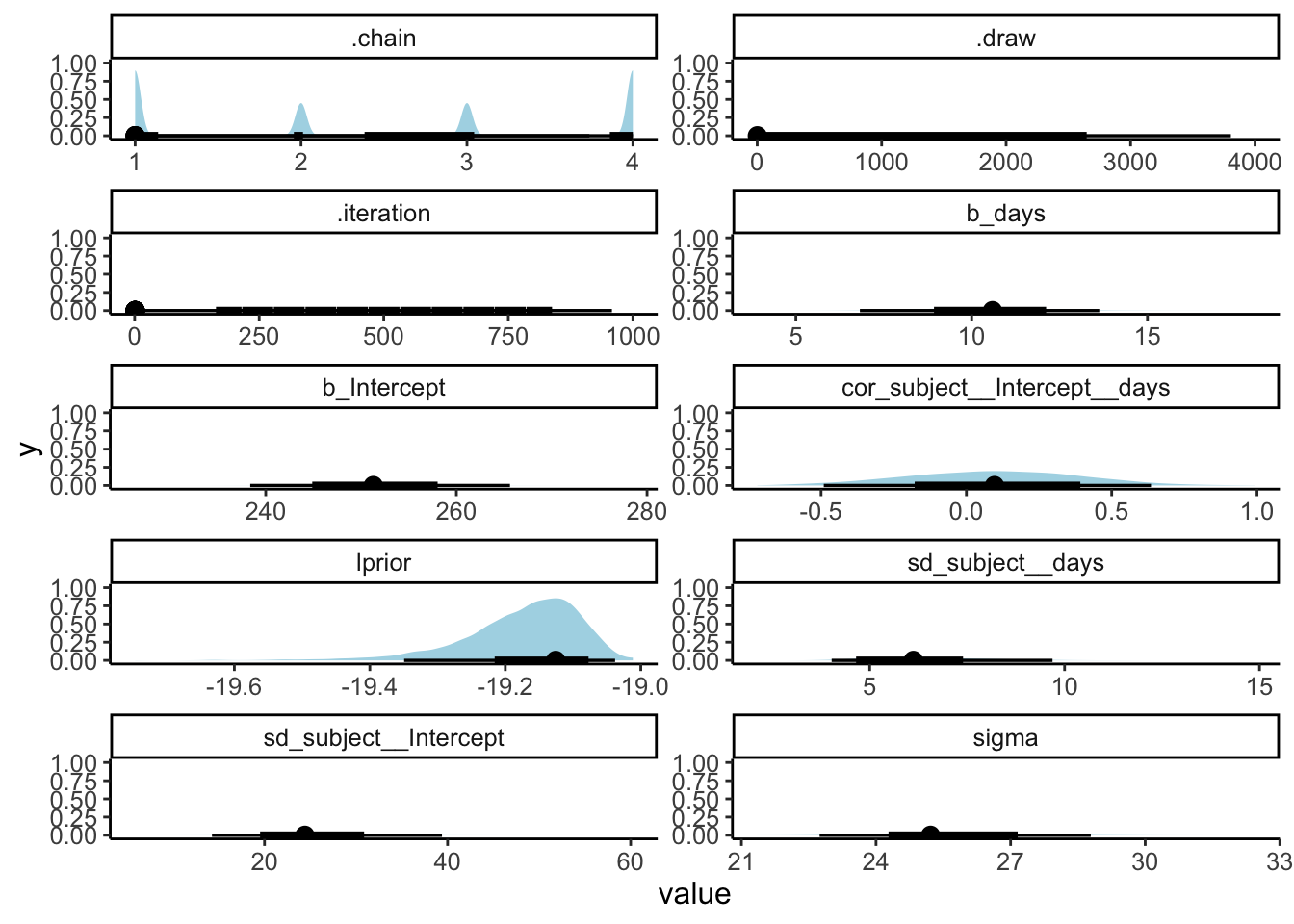

6 ran_pars cond Residual sd__Observa… 25.8 1.54 22.7 28.7 23.5.4.1 Summary of posterior distributions

# all parameters

fit.brm_sleep %>%

as_draws_df() %>%

select(-c(lp__, contains("["))) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = everything(),

names_to = "variable",

values_to = "value") %>%

ggplot(data = .,

mapping = aes(x = value)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval = mode_hdi,

fill = "lightblue") +

facet_wrap(~ variable,

ncol = 2,

scales = "free") +

theme(text = element_text(size = 12))

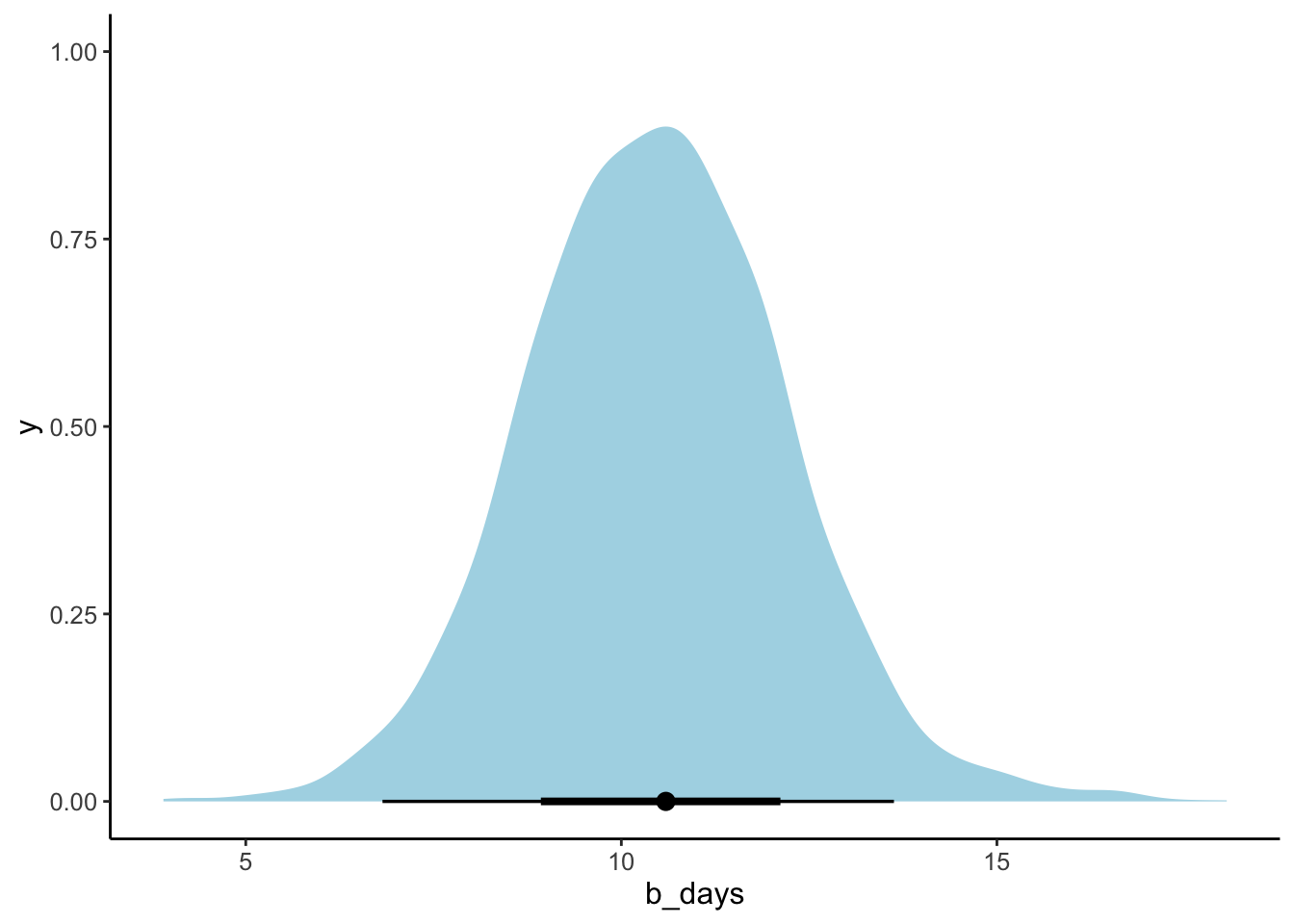

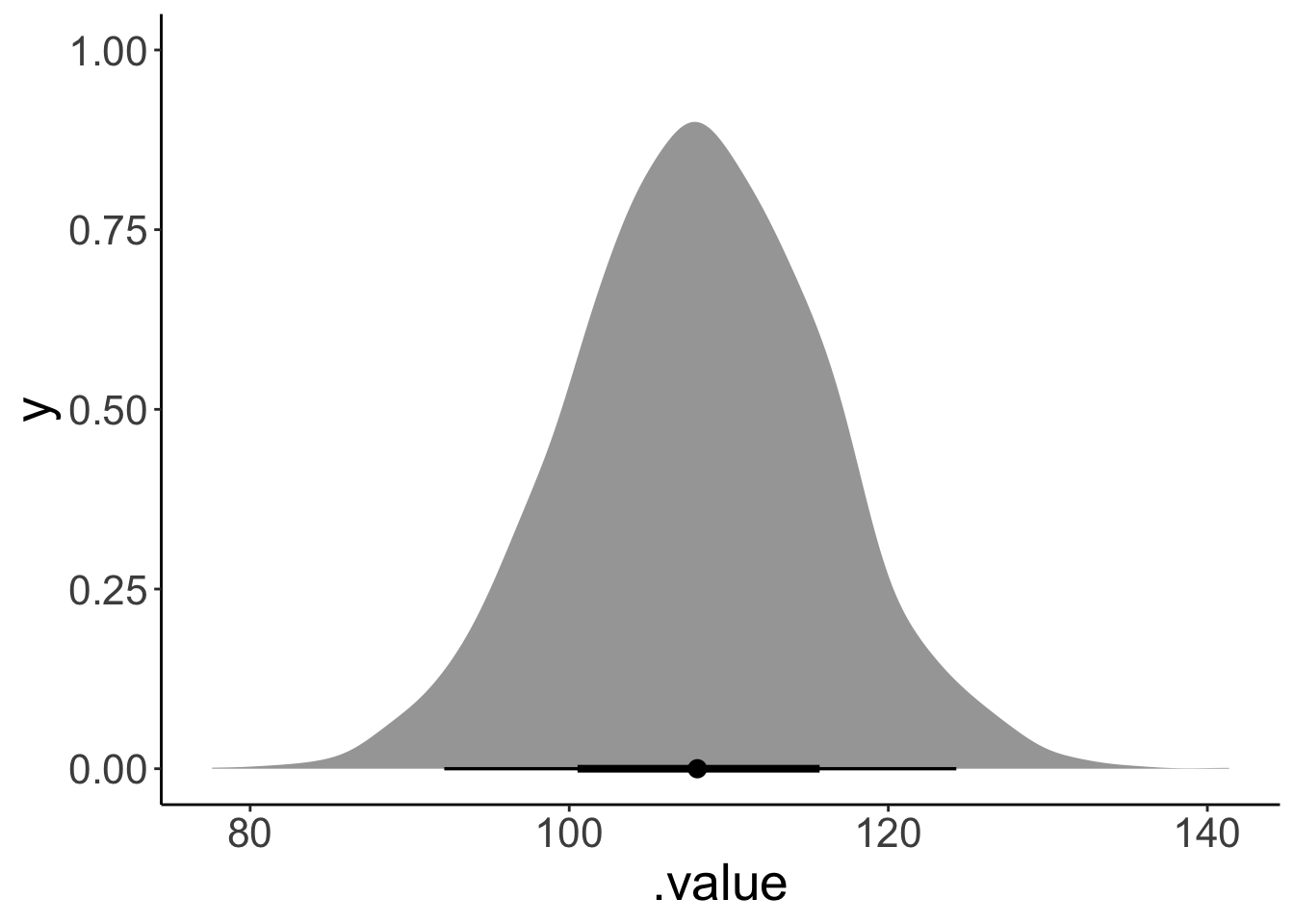

# just the parameter of interest

fit.brm_sleep %>%

as_draws_df() %>%

select(b_days) %>%

ggplot(data = .,

mapping = aes(x = b_days)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval = mode_hdi,

fill = "lightblue") +

theme(text = element_text(size = 12))

23.5.5 5. Test specific hypotheses

Here, we were just interested in how the number of days of sleep deprivation affected reaction time (and we can see that by inspecting the posterior for the days predictor in the model).

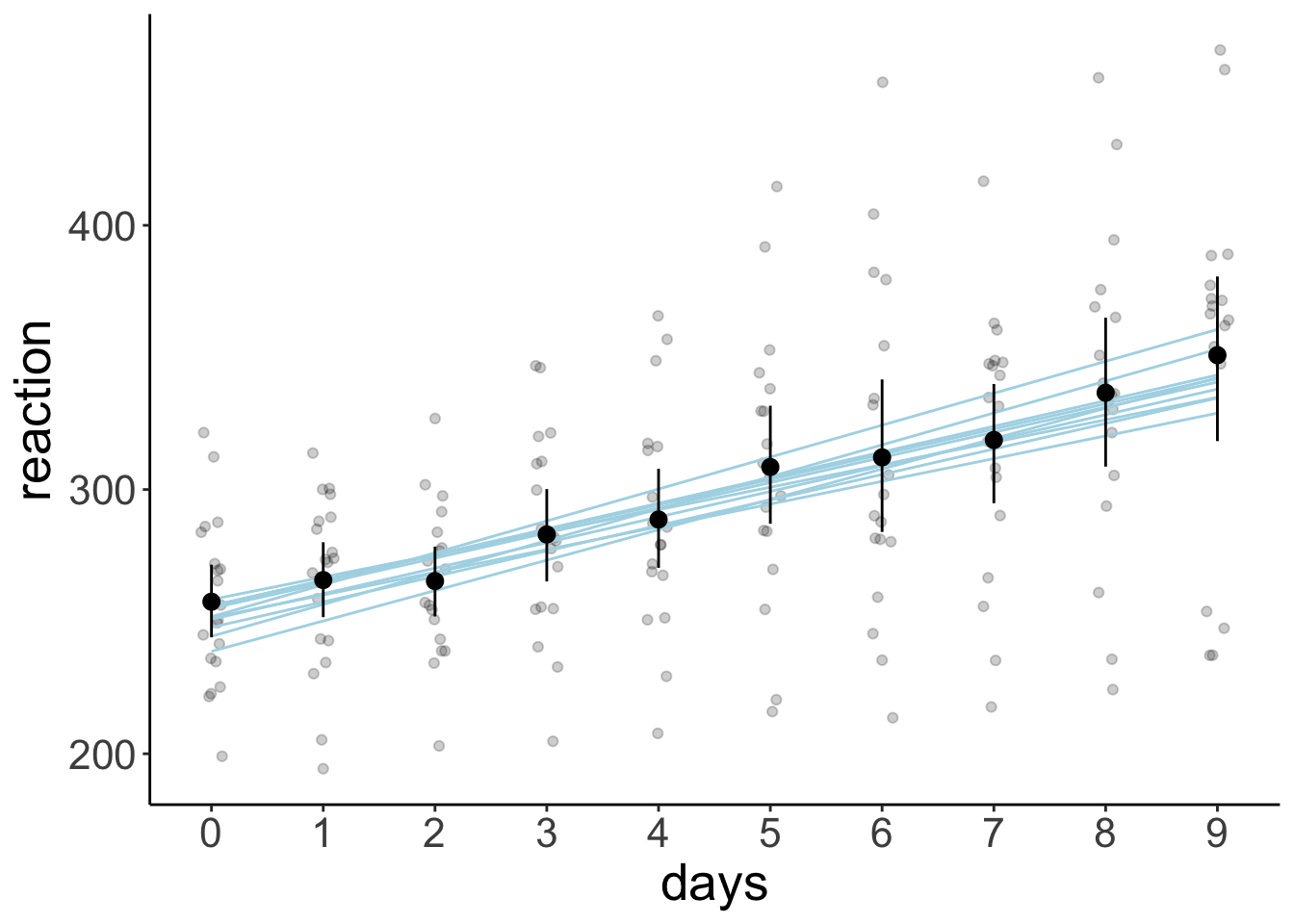

23.5.6 6. Report results

23.5.6.1 Model prediction with posterior draws (aggregate)

df.model = tibble(days = 0:9) %>%

add_linpred_draws(newdata = .,

object = fit.brm_sleep,

ndraws = 10,

seed = 1,

re_formula = NA)

ggplot(data = df.sleep,

mapping = aes(x = days,

y = reaction)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.2,

position = position_jitter(width = 0.1)) +

geom_line(data = df.model,

mapping = aes(y = .linpred,

group = .draw),

color = "lightblue") +

stat_summary(fun.data = "mean_cl_boot") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 0:9)

23.5.6.2 Model prediction with credible intervals (aggregate)

df.model = fit.brm_sleep %>%

fitted(re_formula = NA,

newdata = tibble(days = 0:9)) %>%

as_tibble() %>%

mutate(days = 0:9) %>%

clean_names()

ggplot(data = df.sleep,

mapping = aes(x = days,

y = reaction)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.2,

position = position_jitter(width = 0.1)) +

geom_ribbon(data = df.model,

mapping = aes(y = estimate,

ymin = q2_5,

ymax = q97_5),

fill = "lightblue",

alpha = 0.5) +

geom_line(data = df.model,

mapping = aes(y = estimate),

color = "lightblue",

size = 1) +

stat_summary(fun.data = "mean_cl_boot") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 0:9)Warning: Using `size` aesthetic for lines was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

ℹ Please use `linewidth` instead.

This warning is displayed once every 8 hours.

Call `lifecycle::last_lifecycle_warnings()` to see where this warning was generated.

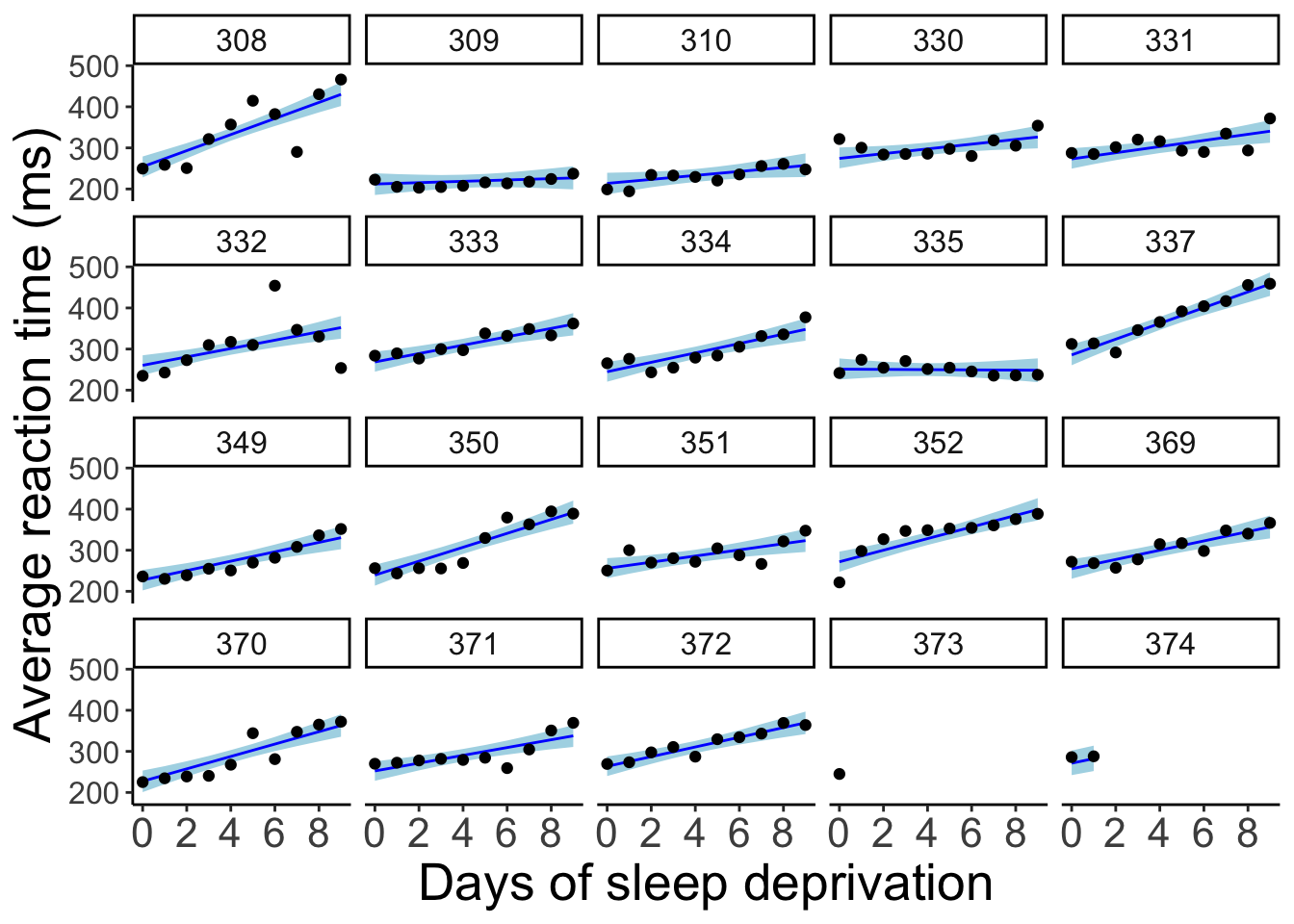

23.5.6.3 Model prediction with credible intervals (individual participants)

fit.brm_sleep %>%

fitted() %>%

as_tibble() %>%

clean_names() %>%

bind_cols(df.sleep) %>%

ggplot(data = .,

mapping = aes(x = days,

y = reaction)) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = q2_5,

ymax = q97_5),

fill = "lightblue") +

geom_line(aes(y = estimate),

color = "blue") +

geom_point() +

facet_wrap(~subject, ncol = 5) +

labs(x = "Days of sleep deprivation",

y = "Average reaction time (ms)") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 0:4 * 2) +

theme(strip.text = element_text(size = 12),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 12))

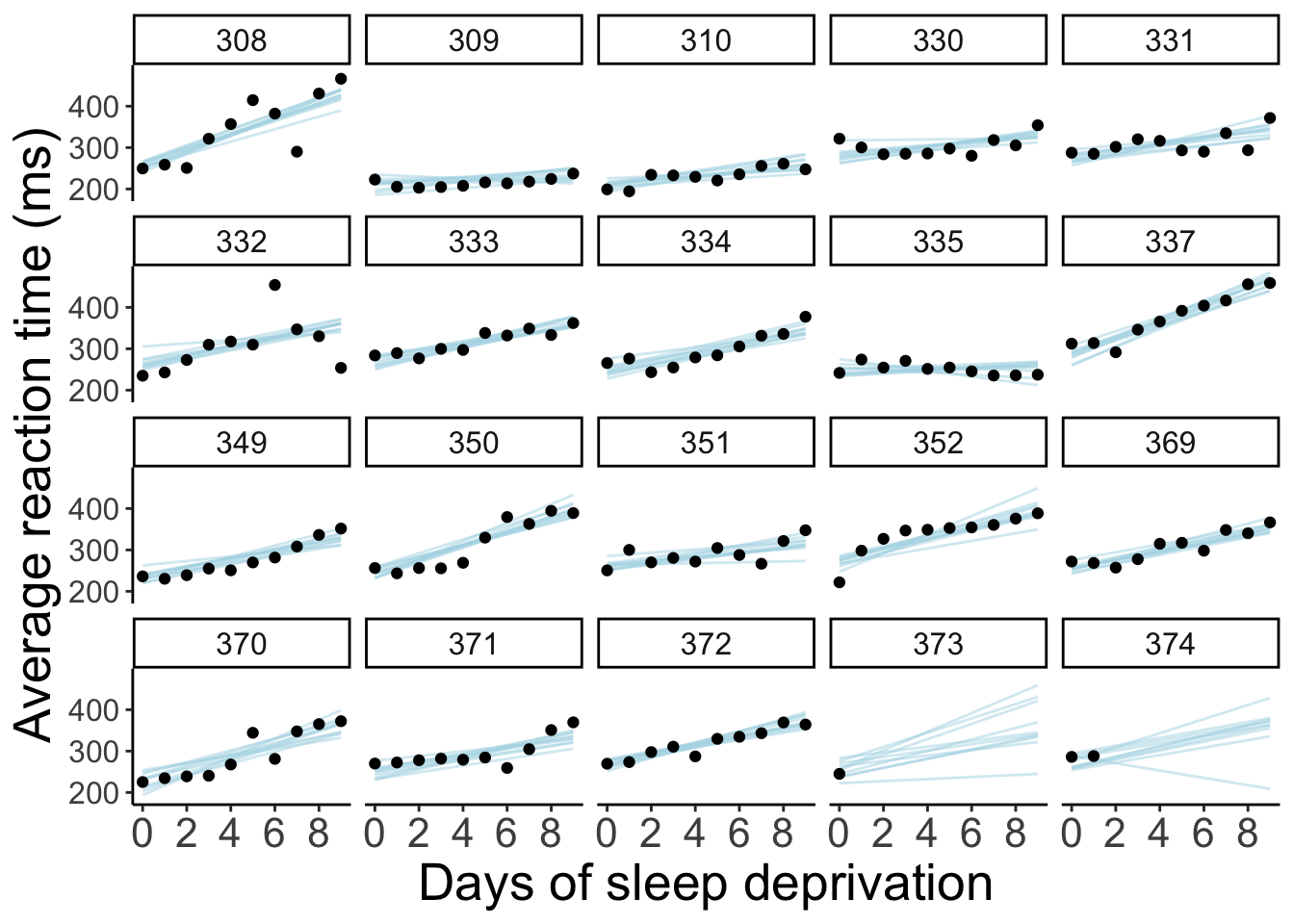

23.5.6.4 Model prediction for random samples

df.model = df.sleep %>%

complete(subject, days) %>%

add_linpred_draws(newdata = .,

object = fit.brm_sleep,

ndraws = 10,

seed = 1)

df.sleep %>%

ggplot(data = .,

mapping = aes(x = days,

y = reaction)) +

geom_line(data = df.model,

aes(y = .linpred,

group = .draw),

color = "lightblue",

alpha = 0.5) +

geom_point() +

facet_wrap(~subject, ncol = 5) +

labs(x = "Days of sleep deprivation",

y = "Average reaction time (ms)") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 0:4 * 2) +

theme(strip.text = element_text(size = 12),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 12))

23.5.6.5 Animated model prediction for random samples

df.model = df.sleep %>%

complete(subject, days) %>%

add_linpred_draws(newdata = .,

object = fit.brm_sleep,

ndraws = 10,

seed = 1)

p = df.sleep %>%

ggplot(data = .,

mapping = aes(x = days,

y = reaction)) +

geom_line(data = df.model,

aes(y = .linpred,

group = .draw),

color = "black") +

geom_point() +

facet_wrap(~subject, ncol = 5) +

labs(x = "Days of sleep deprivation",

y = "Average reaction time (ms)") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 0:4 * 2) +

theme(strip.text = element_text(size = 12),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 12)) +

transition_states(.draw, 0, 1) +

shadow_mark(past = TRUE, alpha = 1/5, color = "gray50")

animate(p, nframes = 10, fps = 1, width = 800, height = 600, res = 96, type = "cairo")Warning: No renderer available. Please install the gifski, av, or magick

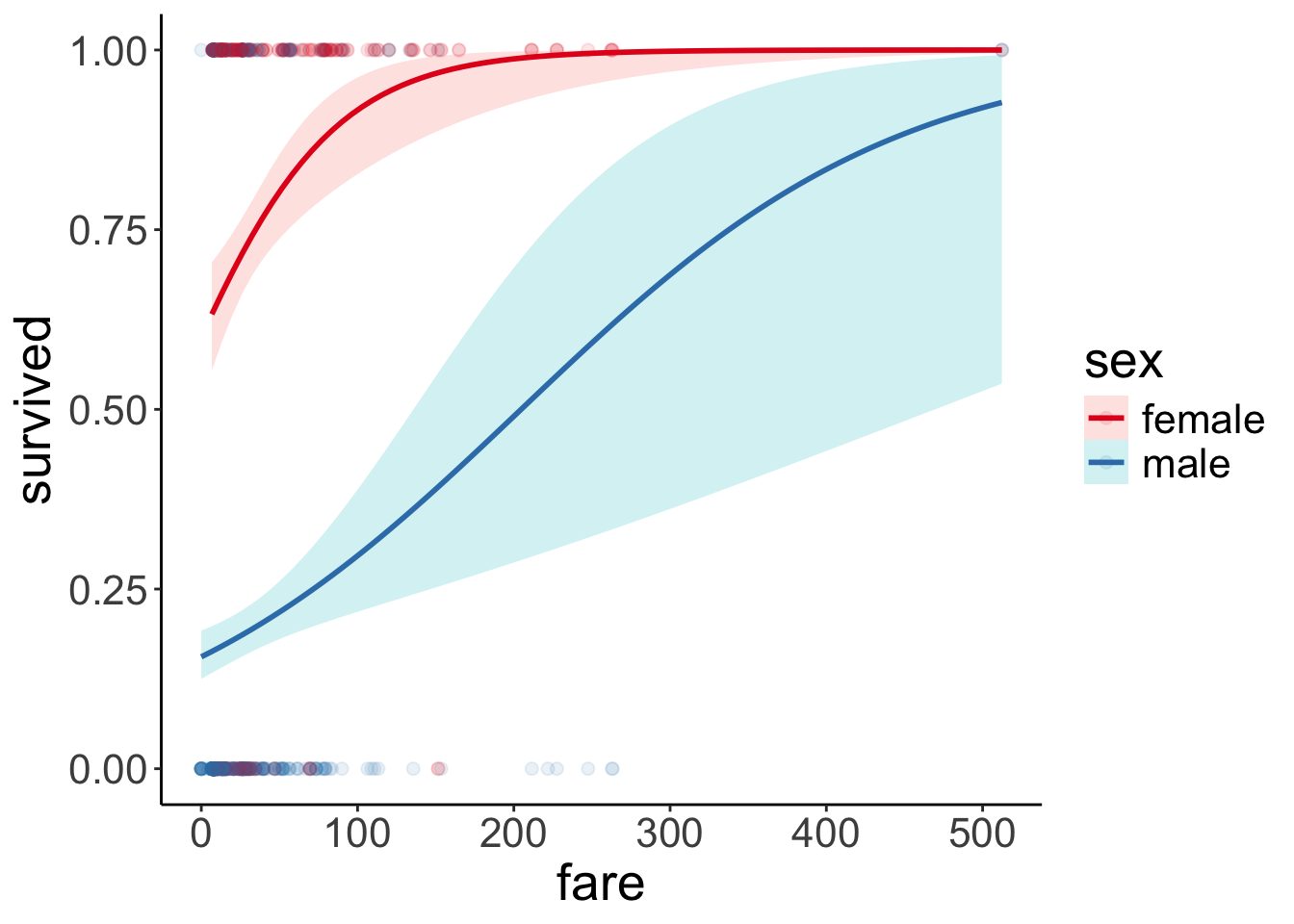

package to create animated output23.6 Titanic study

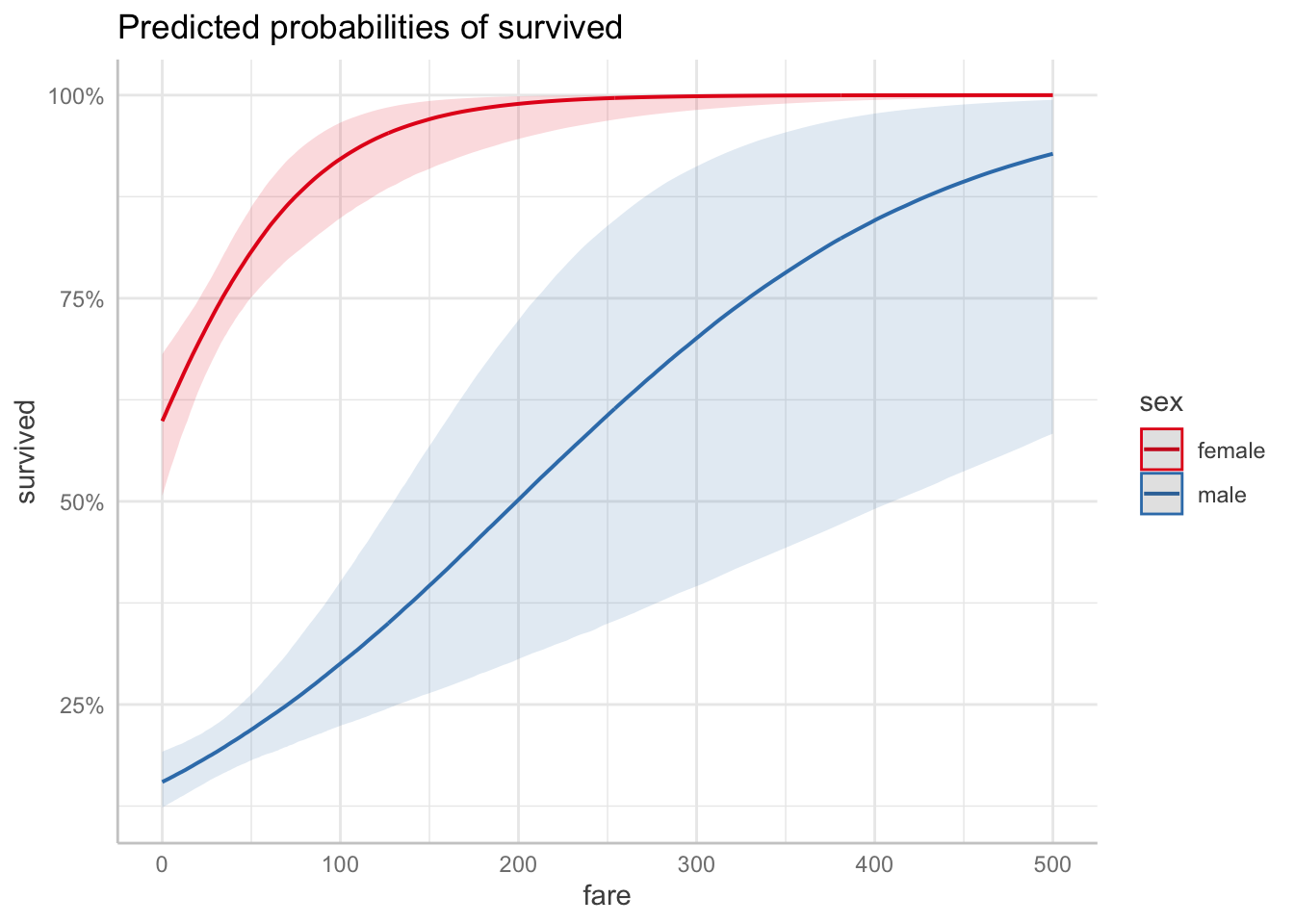

23.6.1 1. Visualize the data

df.titanic %>%

mutate(sex = as.factor(sex)) %>%

ggplot(data = .,

mapping = aes(x = fare,

y = survived,

color = sex)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.1, size = 2) +

geom_smooth(method = "glm",

method.args = list(family = "binomial"),

alpha = 0.2,

aes(fill = sex)) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set1")

23.6.2 2. Specify and fit the model

23.6.2.1 Frequentist analysis

fit.glm_titanic = glm(formula = survived ~ 1 + fare * sex,

family = "binomial",

data = df.titanic)

fit.glm_titanic %>%

summary()

Call:

glm(formula = survived ~ 1 + fare * sex, family = "binomial",

data = df.titanic)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 0.408428 0.189999 2.150 0.031584 *

fare 0.019878 0.005372 3.701 0.000215 ***

sexmale -2.099345 0.230291 -9.116 < 2e-16 ***

fare:sexmale -0.011617 0.005934 -1.958 0.050252 .

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 1186.66 on 890 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 879.85 on 887 degrees of freedom

AIC: 887.85

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 523.6.3 3. Model evaluation

23.6.3.1 a) Did the inference work?

Family: bernoulli

Links: mu = logit

Formula: survived ~ 1 + fare * sex

Data: df.titanic (Number of observations: 891)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 4000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 0.40 0.19 0.03 0.76 1.00 1900 2394

fare 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.03 1.00 1414 1684

sexmale -2.10 0.23 -2.54 -1.64 1.00 1562 1841

fare:sexmale -0.01 0.01 -0.02 -0.00 1.00 1399 1585

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).

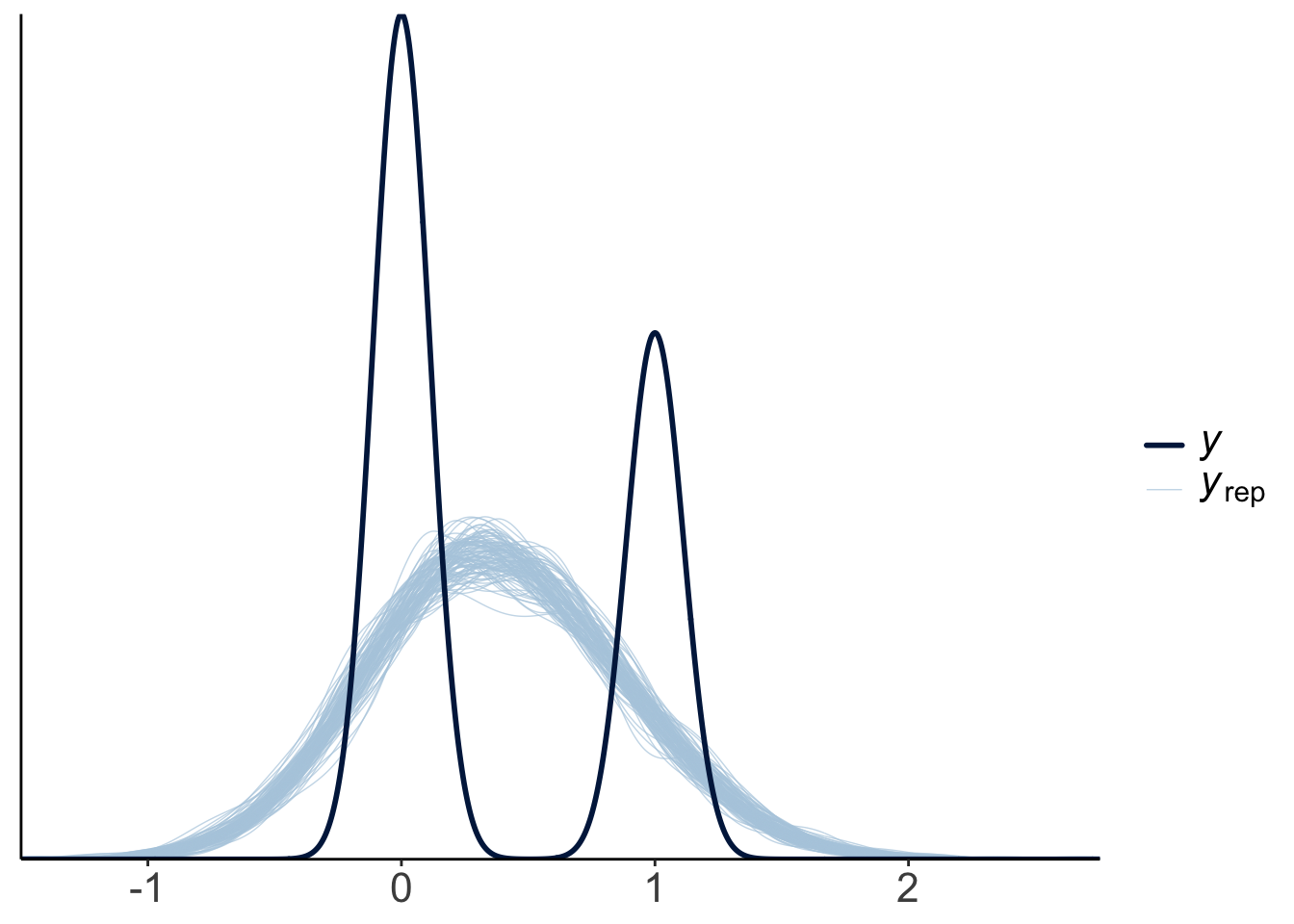

23.6.3.2 b) Visualize model predictions

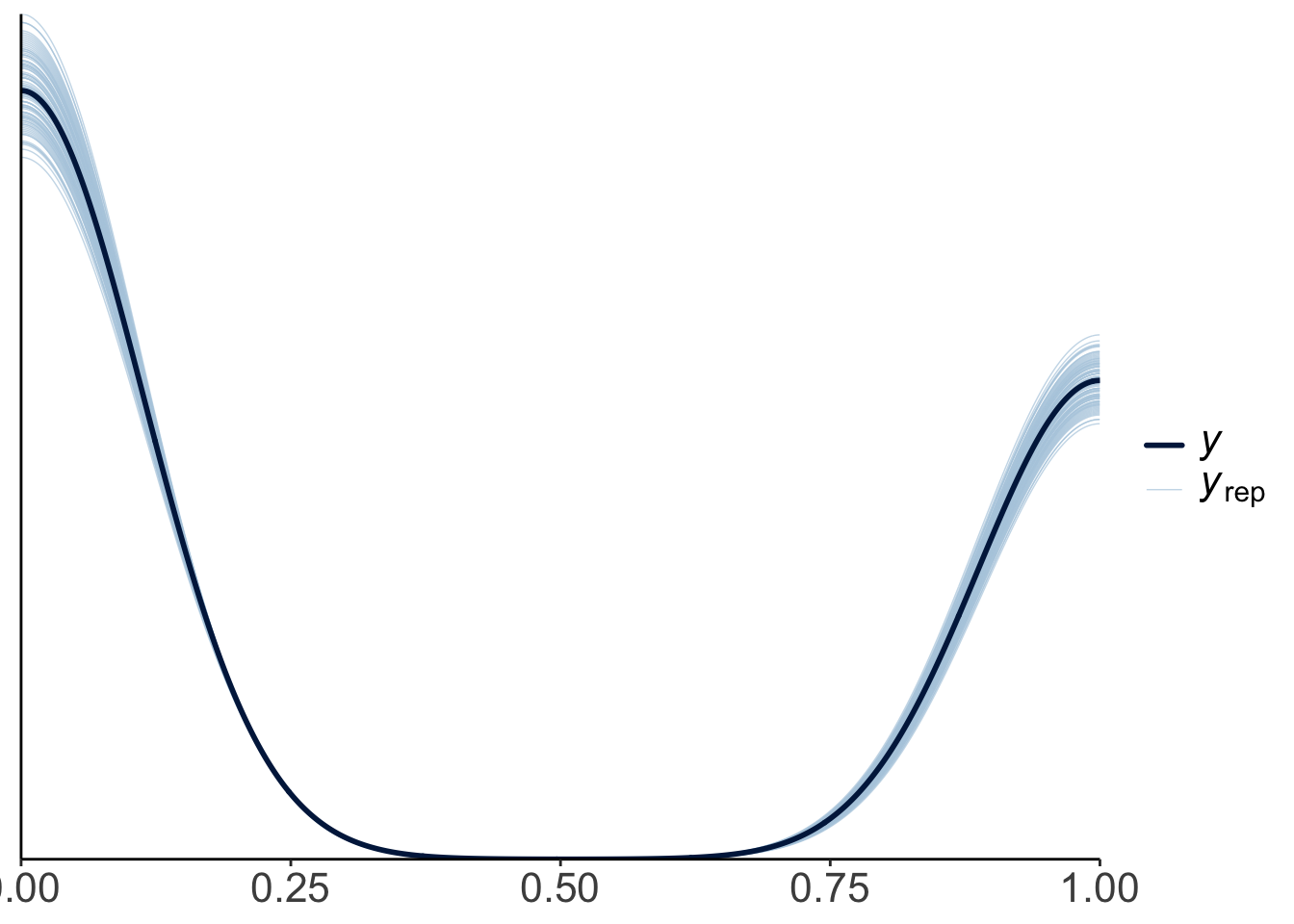

Let’s visualize what the posterior predictive would have looked like for a linear model (instead of a logistic model).

fit.brm_titanic_linear = brm(formula = survived ~ 1 + fare * sex,

data = df.titanic,

file = "cache/brm_titanic_linear",

seed = 1)

pp_check(fit.brm_titanic_linear,

ndraws = 100)

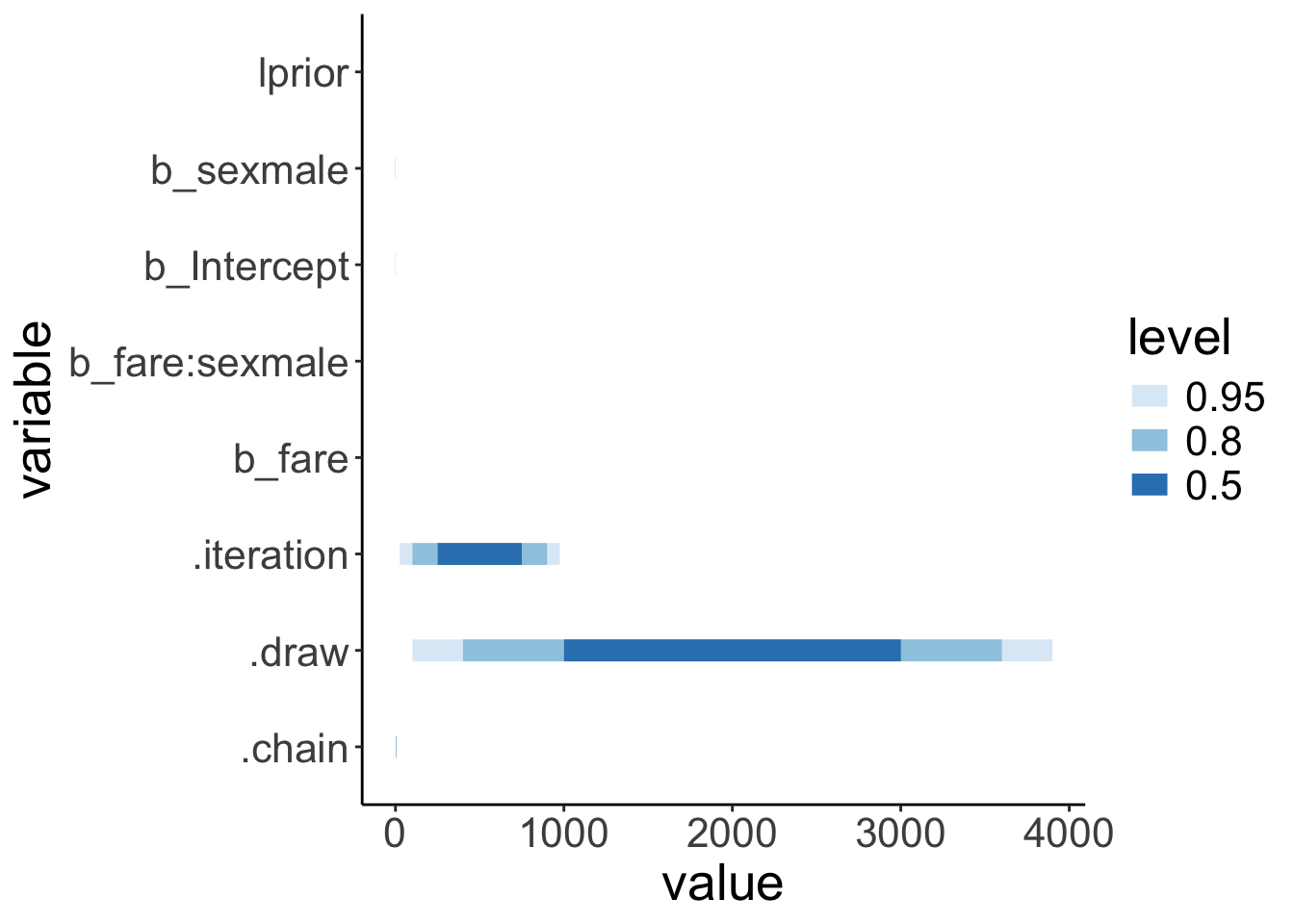

23.6.4 4. Interpret the parameters

fit.brm_titanic %>%

as_draws_df() %>%

select(-lp__) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = everything(),

names_to = "variable",

values_to = "value") %>%

ggplot(data = .,

mapping = aes(y = variable,

x = value)) +

stat_intervalh() +

scale_color_brewer()

23.6.5 5. Test specific hypotheses

Difference between men and women in survival?

NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions$emmeans

sex response lower.HPD upper.HPD

female 0.744 0.691 0.794

male 0.194 0.164 0.229

Point estimate displayed: median

Results are back-transformed from the logit scale

HPD interval probability: 0.95

$contrasts

contrast odds.ratio lower.HPD upper.HPD

female / male 12.1 8.43 16.9

Point estimate displayed: median

Results are back-transformed from the log odds ratio scale

HPD interval probability: 0.95 Difference in how fare affected the chances of survival for men and women?

$emtrends

sex fare.trend lower.HPD upper.HPD

female 0.0206 0.01065 0.0311

male 0.0085 0.00346 0.0135

Point estimate displayed: median

HPD interval probability: 0.95

$contrasts

contrast estimate lower.HPD upper.HPD

female - male 0.0121 0.0011 0.0242

Point estimate displayed: median

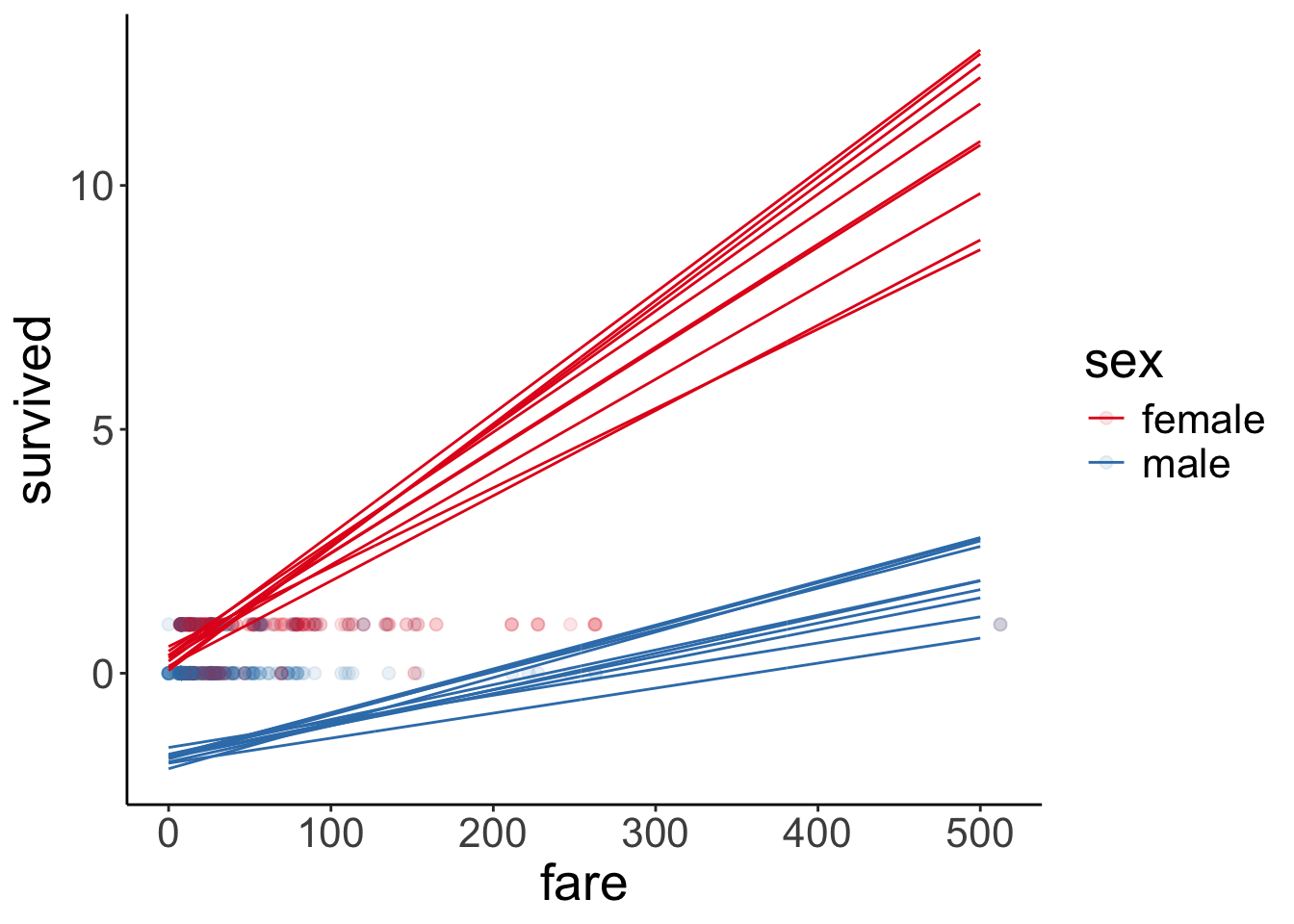

HPD interval probability: 0.95 23.6.6 6. Report results

df.model = add_linpred_draws(newdata = expand_grid(sex = c("female", "male"),

fare = 0:500) %>%

mutate(sex = factor(sex, levels = c("female", "male"))),

object = fit.brm_titanic,

ndraws = 10)

ggplot(data = df.titanic,

mapping = aes(x = fare,

y = survived,

color = sex)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.1, size = 2) +

geom_line(data = df.model %>%

filter(sex == "male"),

aes(y = .linpred,

group = .draw,

color = sex)) +

geom_line(data = df.model %>%

filter(sex == "female"),

aes(y = .linpred,

group = .draw,

color = sex)) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set1")

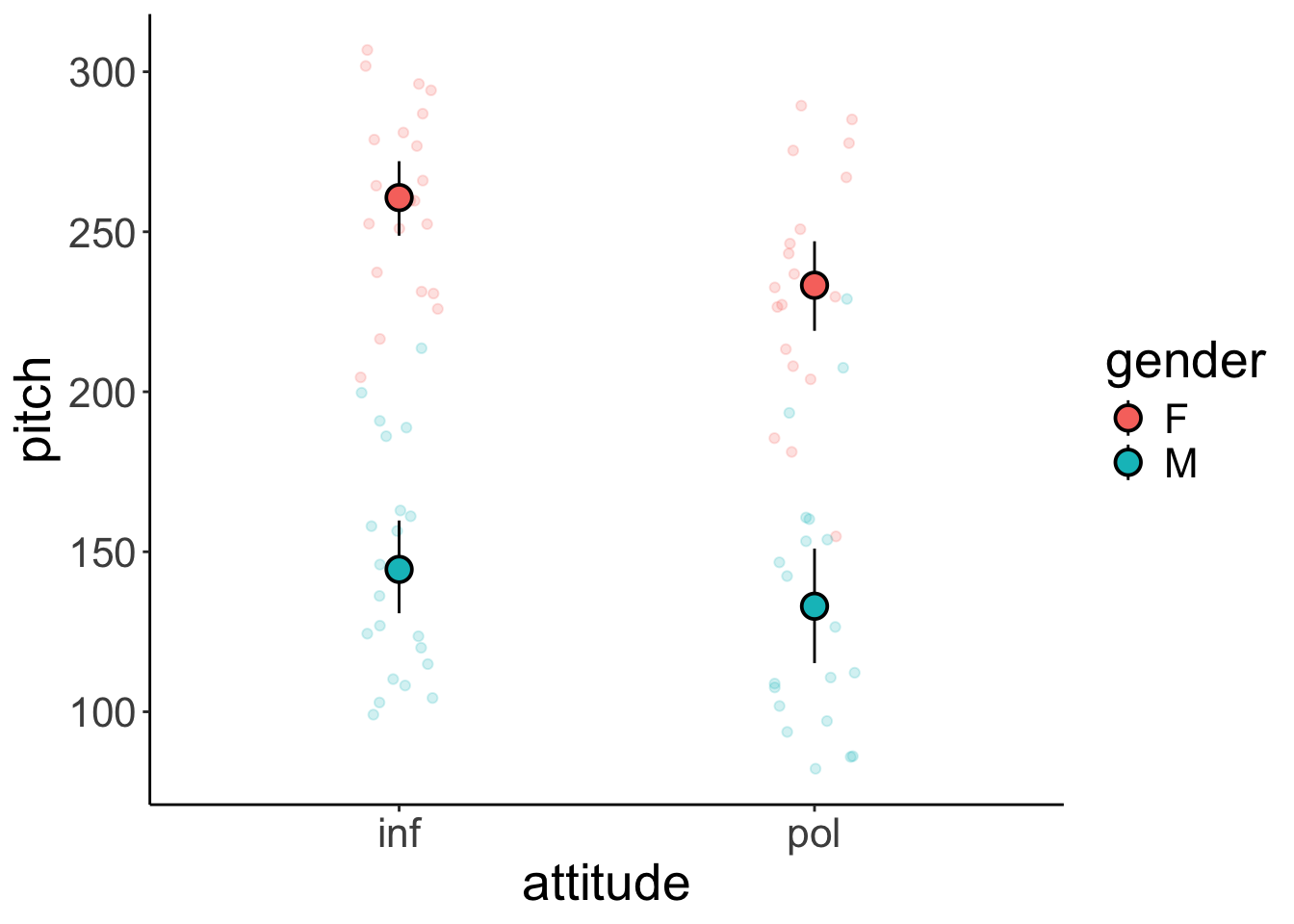

23.7 Politeness data

The data is drawn from Winter and Grawunder (2012), and this section follows the excellent tutorial by Franke and Roettger (2019).

(I’m skipping some of the steps of our recipe for Bayesian data analysis here.)

23.7.1 1. Visualize the data

ggplot(data = df.politeness,

mapping = aes(x = attitude,

y = pitch,

fill = gender,

color = gender)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.2,

position = position_jitter(width = 0.1, height = 0)) +

stat_summary(fun.data = "mean_cl_boot",

shape = 21,

size = 1,

color = "black")Warning: Removed 1 row containing non-finite outside the scale range

(`stat_summary()`).Warning: Removed 1 row containing missing values or values outside the scale

range (`geom_point()`).

23.7.3 5. Test specific hypotheses

23.7.3.1 Frequentist

model term df1 df2 F.ratio p.value

gender 1 79 191.028 <.0001

attitude 1 79 6.170 0.0151

gender:attitude 1 79 1.029 0.3135It looks like there are significant main effects of gender and attitude, but no interaction effect.

Let’s check whether there is a difference in attitude separately for each gender:

gender = F:

contrast estimate SE df t.ratio p.value

inf - pol 27.4 11.0 79 2.489 0.0149

gender = M:

contrast estimate SE df t.ratio p.value

inf - pol 11.5 11.1 79 1.033 0.3048There was a significant difference of attitude for female participants but not for male participants.

23.7.3.2 Bayesian

Let’s whether there was a main effect of gender.

# main effect of gender

fit.brm_polite %>%

emmeans(specs = pairwise ~ gender) %>%

pluck("contrasts")NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions contrast estimate lower.HPD upper.HPD

F - M 108 91.7 124

Results are averaged over the levels of: attitude

Point estimate displayed: median

HPD interval probability: 0.95 Let’s take a look what the full posterior distribution over this contrast looks like:

fit.brm_polite %>%

emmeans(specs = pairwise ~ gender) %>%

pluck("contrasts") %>%

gather_emmeans_draws() %>%

ggplot(mapping = aes(x = .value)) +

stat_halfeye()NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions

Looks neat!

And let’s confirm that we really estimated the main effect here. Let’s fit a model that only has gender as a predictor, and then compare:

fit.brm_polite_gender = brm(formula = pitch ~ 1 + gender,

data = df.politeness,

file = "cache/brm_polite_gender",

seed = 1)

# using the gather_emmeans_draws to get means rather than medians

fit.brm_polite %>%

emmeans(spec = pairwise ~ gender) %>%

pluck("contrasts") %>%

gather_emmeans_draws() %>%

mean_hdi()NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions# A tibble: 1 × 7

contrast .value .lower .upper .width .point .interval

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 F - M 108. 91.9 124. 0.95 mean hdi # A tibble: 2 × 5

term Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Intercept 247. 5.72 236. 258.

2 genderM -108. 8.16 -124. -92.3Yip, both of these methods give us the same result (the sign is flipped but that’s just because emmeans computed F-M, whereas the other method computed M-F)! Again, the emmeans() route is more convenient because we can more easily check for several main effects (and take a look at specific contrast, too).

# main effect attitude

fit.brm_polite %>%

emmeans(specs = pairwise ~ attitude) %>%

pluck("contrasts")NOTE: Results may be misleading due to involvement in interactions contrast estimate lower.HPD upper.HPD

inf - pol 19.8 5.16 35.9

Results are averaged over the levels of: gender

Point estimate displayed: median

HPD interval probability: 0.95 # effect of attitude separately for each gender

fit.brm_polite %>%

emmeans(specs = pairwise ~ attitude | gender) %>%

pluck("contrasts")gender = F:

contrast estimate lower.HPD upper.HPD

inf - pol 27.9 5.96 49.5

gender = M:

contrast estimate lower.HPD upper.HPD

inf - pol 12.0 -9.29 34.2

Point estimate displayed: median

HPD interval probability: 0.95 # in case you want the means instead of medians

fit.brm_polite %>%

emmeans(specs = pairwise ~ attitude | gender) %>%

pluck("contrasts") %>%

gather_emmeans_draws() %>%

mean_hdi()# A tibble: 2 × 8

contrast gender .value .lower .upper .width .point .interval

<fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 inf - pol F 27.8 5.96 49.5 0.95 mean hdi

2 inf - pol M 11.9 -9.29 34.2 0.95 mean hdi Here is a way to visualize the contrasts:

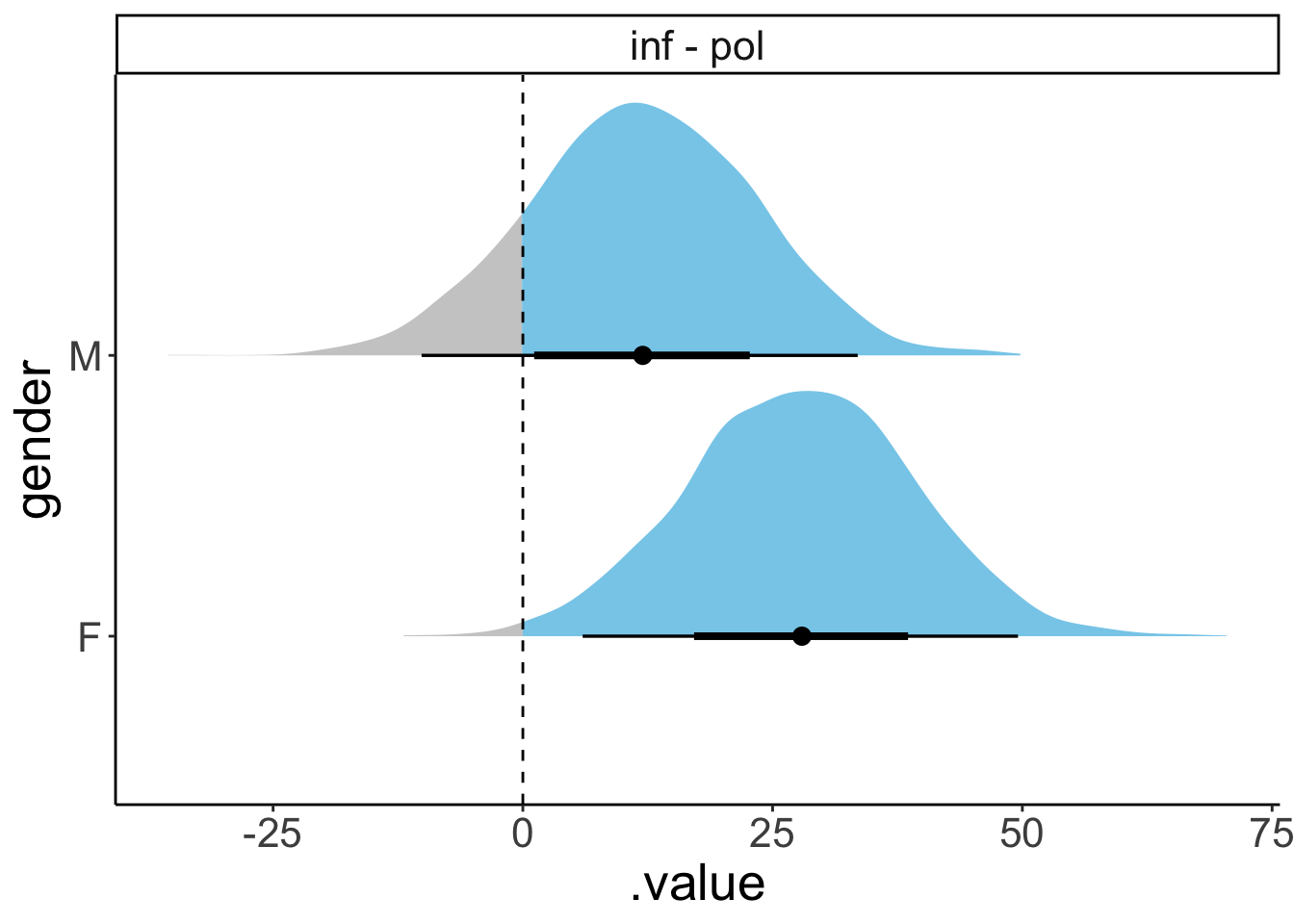

fit.brm_polite %>%

emmeans(specs = pairwise ~ attitude | gender) %>%

pluck("contrasts") %>%

gather_emmeans_draws() %>%

ggplot(aes(x = .value,

y = gender,

fill = stat(x > 0))) +

facet_wrap(~ contrast) +

stat_halfeye(show.legend = F) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0,

linetype = 2) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("gray80", "skyblue"))Warning: `stat(x > 0)` was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

ℹ Please use `after_stat(x > 0)` instead.

This warning is displayed once every 8 hours.

Call `lifecycle::last_lifecycle_warnings()` to see where this warning was generated.

Here is one way to check whether there was an interaction between attitude and gender (see this vignette for more info).

fit.brm_polite %>%

emmeans(pairwise ~ attitude | gender) %>%

pluck("emmeans") %>%

contrast(interaction = c("consec"),

by = NULL) attitude_consec gender_consec estimate lower.HPD upper.HPD

pol - inf M - F 16.1 -15.1 47.2

Point estimate displayed: median

HPD interval probability: 0.95 23.9 Session info

Information about this R session including which version of R was used, and what packages were loaded.

R version 4.4.2 (2024-10-31)

Platform: aarch64-apple-darwin20

Running under: macOS Sequoia 15.2

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.4-arm64/Resources/lib/libRblas.0.dylib

LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.4-arm64/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib; LAPACK version 3.12.0

locale:

[1] en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/C/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8

time zone: America/Los_Angeles

tzcode source: internal

attached base packages:

[1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

other attached packages:

[1] lubridate_1.9.3 forcats_1.0.0 stringr_1.5.1

[4] dplyr_1.1.4 purrr_1.0.2 readr_2.1.5

[7] tidyr_1.3.1 tibble_3.2.1 tidyverse_2.0.0

[10] transformr_0.1.5.9000 parameters_0.24.0 gganimate_1.0.9

[13] titanic_0.1.0 ggeffects_2.0.0 emmeans_1.10.6

[16] car_3.1-3 carData_3.0-5 afex_1.4-1

[19] lme4_1.1-35.5 Matrix_1.7-1 modelr_0.1.11

[22] bayesplot_1.11.1 broom.mixed_0.2.9.6 GGally_2.2.1

[25] ggplot2_3.5.1 patchwork_1.3.0 brms_2.22.0

[28] Rcpp_1.0.13 tidybayes_3.0.7 janitor_2.2.1

[31] kableExtra_1.4.0 knitr_1.49

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] svUnit_1.0.6 shinythemes_1.2.0 later_1.3.2

[4] splines_4.4.2 datawizard_0.13.0 xts_0.14.0

[7] rpart_4.1.23 lifecycle_1.0.4 sf_1.0-19

[10] StanHeaders_2.32.9 globals_0.16.3 lattice_0.22-6

[13] vroom_1.6.5 MASS_7.3-64 crosstalk_1.2.1

[16] insight_1.0.0 ggdist_3.3.2 backports_1.5.0

[19] magrittr_2.0.3 Hmisc_5.2-1 sass_0.4.9

[22] rmarkdown_2.29 jquerylib_0.1.4 yaml_2.3.10

[25] httpuv_1.6.15 pkgbuild_1.4.4 DBI_1.2.3

[28] minqa_1.2.7 RColorBrewer_1.1-3 abind_1.4-5

[31] nnet_7.3-19 tensorA_0.36.2.1 tweenr_2.0.3

[34] inline_0.3.19 listenv_0.9.1 units_0.8-5

[37] bridgesampling_1.1-2 parallelly_1.37.1 svglite_2.1.3

[40] codetools_0.2-20 DT_0.33 xml2_1.3.6

[43] tidyselect_1.2.1 rstanarm_2.32.1 farver_2.1.2

[46] matrixStats_1.3.0 stats4_4.4.2 base64enc_0.1-3

[49] jsonlite_1.8.8 e1071_1.7-14 Formula_1.2-5

[52] survival_3.7-0 systemfonts_1.1.0 tools_4.4.2

[55] progress_1.2.3 glue_1.8.0 gridExtra_2.3

[58] mgcv_1.9-1 xfun_0.49 distributional_0.4.0

[61] loo_2.8.0 withr_3.0.2 numDeriv_2016.8-1.1

[64] fastmap_1.2.0 boot_1.3-31 fansi_1.0.6

[67] shinyjs_2.1.0 digest_0.6.36 mime_0.12

[70] timechange_0.3.0 R6_2.5.1 estimability_1.5.1

[73] colorspace_2.1-0 gtools_3.9.5 lpSolve_5.6.20

[76] markdown_1.13 threejs_0.3.3 utf8_1.2.4

[79] generics_0.1.3 data.table_1.15.4 class_7.3-22

[82] prettyunits_1.2.0 htmlwidgets_1.6.4 ggstats_0.6.0

[85] pkgconfig_2.0.3 dygraphs_1.1.1.6 gtable_0.3.5

[88] furrr_0.3.1 htmltools_0.5.8.1 bookdown_0.42

[91] scales_1.3.0 posterior_1.6.0 snakecase_0.11.1

[94] rstudioapi_0.16.0 tzdb_0.4.0 reshape2_1.4.4

[97] coda_0.19-4.1 checkmate_2.3.1 nlme_3.1-166

[100] curl_5.2.1 nloptr_2.1.1 proxy_0.4-27

[103] cachem_1.1.0 zoo_1.8-12 sjlabelled_1.2.0

[106] KernSmooth_2.23-24 miniUI_0.1.1.1 parallel_4.4.2

[109] foreign_0.8-87 pillar_1.9.0 grid_4.4.2

[112] vctrs_0.6.5 shinystan_2.6.0 promises_1.3.0

[115] arrayhelpers_1.1-0 xtable_1.8-4 cluster_2.1.6

[118] htmlTable_2.4.2 evaluate_0.24.0 mvtnorm_1.2-5

[121] cli_3.6.3 compiler_4.4.2 rlang_1.1.4

[124] crayon_1.5.3 rstantools_2.4.0 labeling_0.4.3

[127] classInt_0.4-10 plyr_1.8.9 stringi_1.8.4

[130] rstan_2.32.6 viridisLite_0.4.2 QuickJSR_1.3.0

[133] lmerTest_3.1-3 munsell_0.5.1 colourpicker_1.3.0

[136] Brobdingnag_1.2-9 bayestestR_0.15.0 V8_5.0.0

[139] hms_1.1.3 bit64_4.0.5 future_1.33.2

[142] shiny_1.9.1 haven_2.5.4 igraph_2.0.3

[145] broom_1.0.7 RcppParallel_5.1.8 bslib_0.7.0

[148] bit_4.0.5